This article is part of the

Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which explains how heat transfer behavior is translated into

engineering calculations and design logic.

It follows the earlier discussion on quantifying heat transfer in:

How Heat Transfer Is Quantified in Process Plants

.

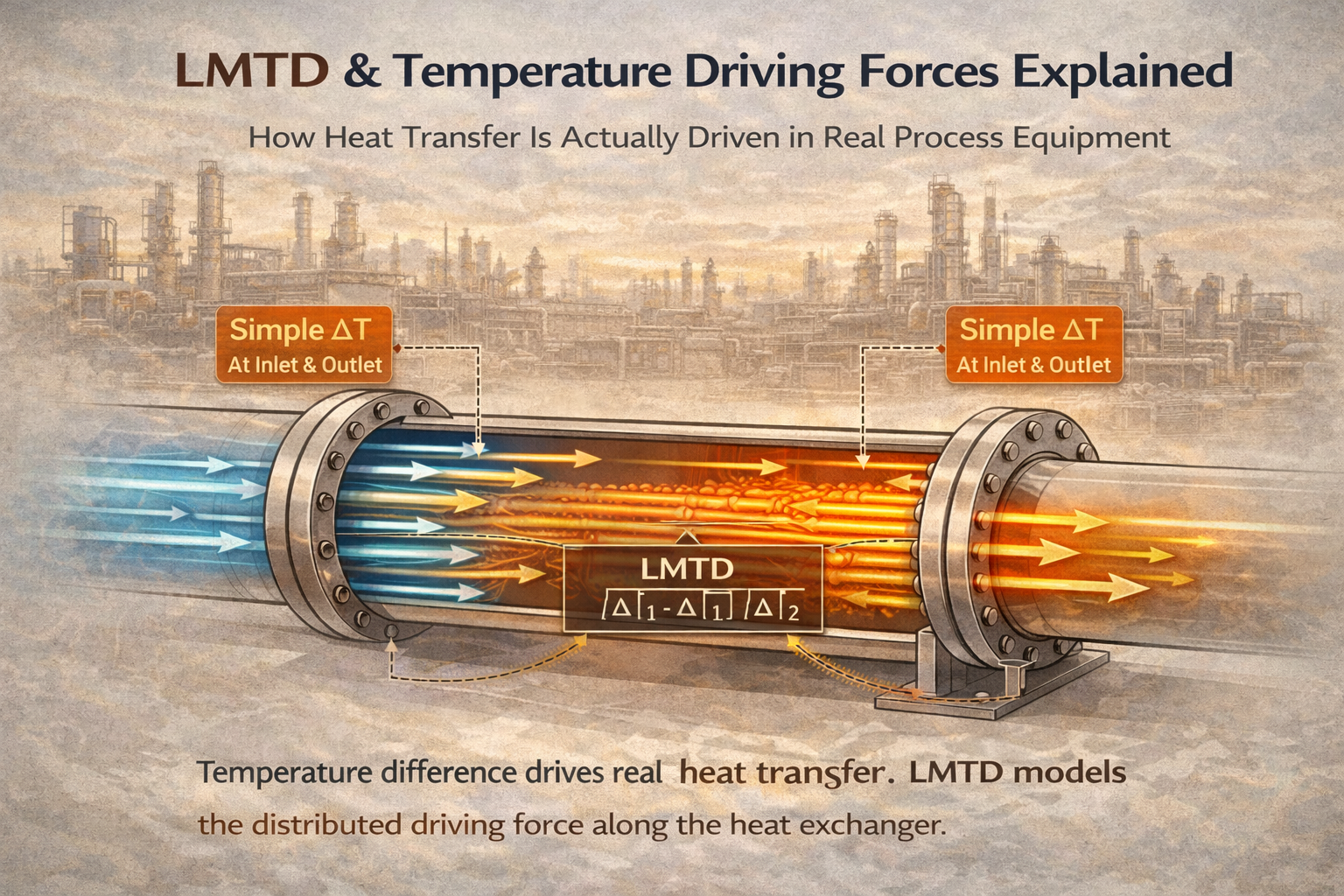

Building on that foundation, this article explains how temperature driving

forces are defined and why LMTD is used in practical heat exchanger design.

How Heat Transfer Is Actually Driven in Real Process Equipment

Every heat transfer calculation in process plants ultimately depends on one thing:

temperature driving force.

No matter how large the exchanger, how good the material, or how high the utility flow, heat transfer cannot occur unless a temperature difference exists.

LMTD — the Log Mean Temperature Difference — is the most widely used way of representing that driving force. It appears simple, familiar, and mathematical.

Yet in real plants, LMTD is one of the most misunderstood concepts in heat transfer.

This article explains what LMTD really represents, why it exists, how it connects to physical driving forces, and why misusing it leads to exchanger underperformance, control problems, and failed debottlenecking efforts.

Table of Contents

Temperature Difference Is the True Driving Force

Heat transfer does not respond to equations.

It responds to local temperature difference.

At every point in a heat exchanger:

- one fluid is hotter,

- one fluid is colder,

- heat flows locally according to that local difference.

This difference:

- changes along the exchanger length,

- changes with flow arrangement,

- collapses near pinch points,

- spikes near inlets.

There is no single temperature difference that represents the whole exchanger.

LMTD exists to approximate this distributed driving force in a usable form.

Why Simple ΔT Fails Immediately

A simple temperature difference (hot in – cold out, or hot out – cold in) assumes:

- temperature difference is constant,

- heat transfer rate is uniform,

- driving force does not change with position.

None of these are true in real exchangers.

Using a simple ΔT:

- overestimates driving force in some regions,

- underestimates it in others,

- hides pinch points,

- gives false confidence about margin.

Simple ΔT is not wrong mathematically — it is physically incomplete.

What LMTD Actually Represents

LMTD is not an “average temperature difference” in the intuitive sense.

It is a logarithmic weighting of temperature difference that reflects:

- high driving force regions contributing more heat,

- low driving force regions limiting performance.

LMTD mathematically accounts for the fact that:

- most heat transfer occurs where ΔT is high,

- overall performance is constrained where ΔT is low.

This makes LMTD a better representation of effective driving force than any simple average.

LMTD Is a Model of Spatial Reality

In real exchangers:

- temperature difference is highest at one end,

- lowest at the other,

- continuously varying in between.

LMTD compresses this spatial variation into a single value that preserves:

- total heat transfer rate,

- correct weighting of local driving forces.

This is why LMTD works well for:

- steady-state design,

- single-phase heat exchange,

- well-behaved flow arrangements.

But it is still a model, not the physical process itself.

Why Flow Arrangement Changes LMTD

Counter-current, co-current, and cross-flow exchangers have different temperature profiles.

As a result:

- the same inlet and outlet temperatures produce different local ΔT distributions,

- different effective driving forces exist,

- different exchanger sizes are required.

LMTD captures this difference naturally.

This is why:

- counter-current exchangers are usually more efficient,

- co-current exchangers struggle near outlet,

- cross-flow exchangers require correction factors.

LMTD is sensitive to how fluids meet, not just how hot or cold they are.

LMTD Does Not Create Heat Transfer Capability

A critical misconception is treating LMTD as something that can be “adjusted” operationally.

LMTD does not create heat transfer.

It only describes available driving force.

If LMTD is small:

- no amount of area will fix local pinch limitations,

- increasing flow may worsen approach,

- utilities may saturate.

If LMTD collapses locally:

- heat transfer stops there first,

- control becomes unstable,

- fouling accelerates.

Plants fail at minimum local ΔT, not at average LMTD.

Why LMTD Is a Design Tool, Not a Guarantee

Designers use LMTD to size exchangers under assumed conditions:

- clean surfaces,

- steady flow,

- expected temperatures.

Operation introduces:

- fouling,

- flow maldistribution,

- seasonal changes,

- partial loads.

All of these distort local temperature profiles.

As conditions drift:

- true effective driving force deviates from design LMTD,

- margins shrink,

- performance becomes fragile.

This is why exchangers that “met design” struggle years later.

Driving Force Collapse Is the Real Limitation

Most exchanger problems are not area problems.

They are driving force problems.

Common symptoms:

- outlet temperature stuck near approach limit,

- large utility consumption for small duty increase,

- sensitivity to minor fouling,

- control oscillation near limits.

All of these indicate local driving force collapse.

LMTD hides where collapse occurs unless profiles are examined.

LMTD and Temperature Pinch Are Linked

Temperature pinch is the location where:

- hot and cold streams approach each other closely,

- local ΔT becomes minimal,

- heat transfer resistance explodes.

LMTD averages over the entire exchanger, but pinch governs capacity.

This explains why:

- exchangers appear oversized but underperform,

- small fouling causes sudden loss of duty,

- debottlenecking fails without changing approach temperatures.

Design must respect pinch, not just LMTD.

Owner Perspective: Why LMTD Misuse Costs Money

From an ownership standpoint, misunderstanding LMTD leads to:

- oversized exchangers that still bottleneck,

- repeated cleaning without root cause removal,

- excessive utility consumption,

- failed revamps and expansions.

Plants pay for:

- false confidence,

- hidden pinch points,

- misunderstood margins.

Correct understanding of driving force prevents these losses.

Final Perspective

LMTD is not a formula to memorize.

It is a compact description of how temperature driving force is distributed inside equipment.

Used correctly, it:

- enables sound design,

- highlights efficiency advantages,

- supports realistic sizing.

Used blindly, it:

- hides local limitations,

- masks pinch points,

- creates fragile systems.

Understanding LMTD is not about mathematics.

It is about respecting how heat actually moves through process equipment.

And that understanding is essential for anyone responsible for reliable heat exchanger performance in real plants.

We have discussed how temperature differences drive heat transfer and why a

simple inlet or outlet temperature difference is often misleading in real

equipment.

The next step is to see how the Log Mean Temperature Difference is developed

and applied in a clear, systematic way.

This article walks through the LMTD concept one step at a time, showing how it

is calculated, what assumptions are involved, and how engineers use it in

practical heat exchanger design.