This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants series, which explains how heat transfer behavior is translated into engineering calculations and design decisions.

It supports the broader discussion on quantifying heat transfer presented in:

How Heat Transfer Is Quantified in Process Plants

.

This article focuses specifically on the practical meaning of heat duty and how engineers interpret it in real plant calculations.

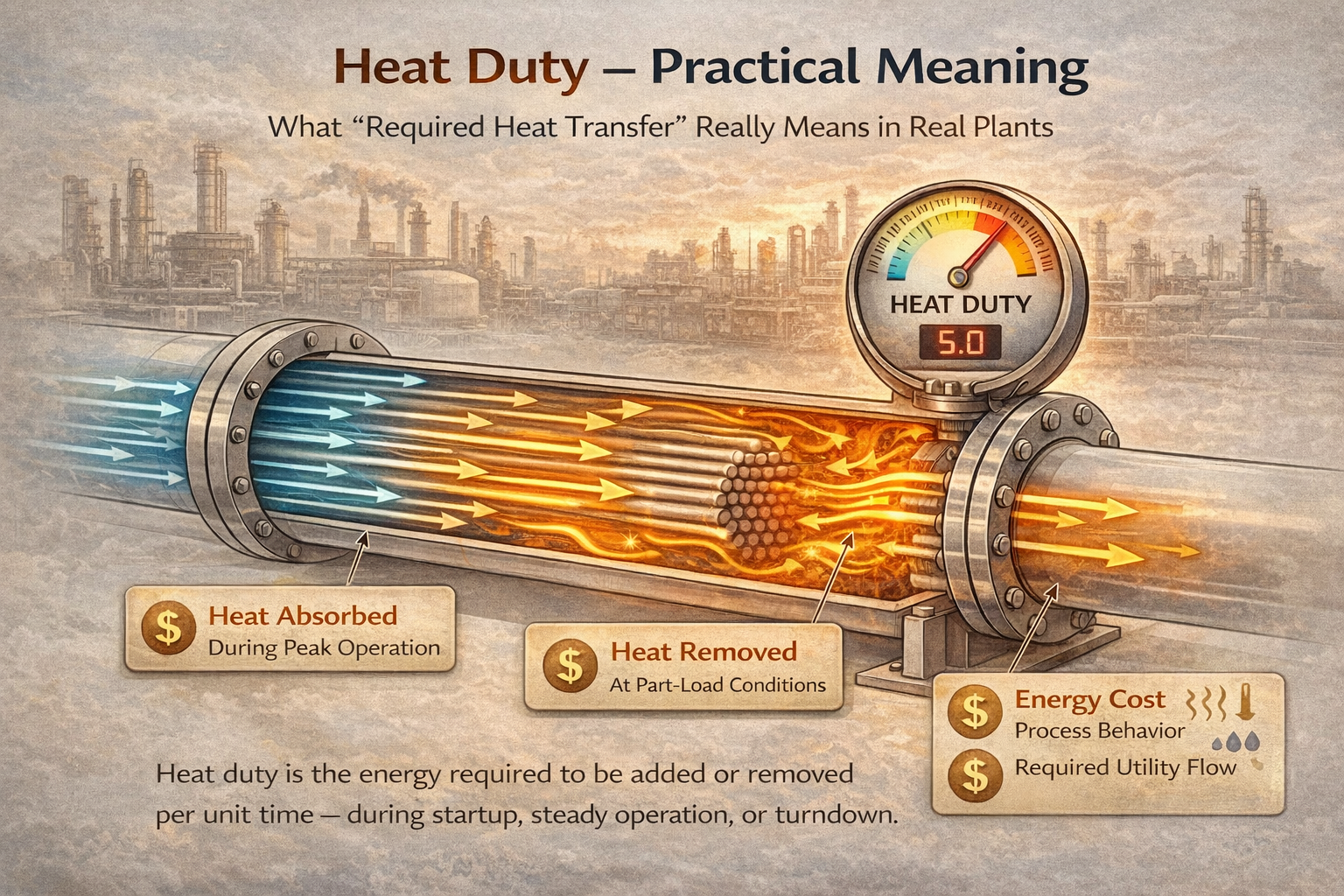

What “Required Heat Transfer” Really Means in Real Plants

In process engineering, heat duty is one of the most frequently used terms. It appears in datasheets, specifications, simulations, and operating discussions.

Yet despite its frequent use, heat duty is often poorly understood in practice.

Many plant problems originate not because heat duty was calculated incorrectly, but because its practical meaning was misunderstood.

This article explains what heat duty actually represents in real process plants, how it should be interpreted, and why treating it as a fixed number leads to recurring operational issues.

Table of Contents

Heat Duty Is an Energy Rate, Not a Temperature

At its simplest, heat duty answers one question:

How much energy must be added or removed per unit time?

Heat duty is not:

- a temperature,

- a temperature difference,

- a surface area,

- a heat transfer coefficient.

It is an energy flow requirement.

This distinction matters because:

- temperature describes condition,

- heat duty describes capability.

Confusing the two leads to incorrect conclusions about equipment performance.

Why Heat Duty Comes First in Design Thinking

In real plant design, heat duty is the first thermal quantity engineers establish.

Before selecting:

- exchanger type,

- utility system,

- firing rate,

- cooling capacity,

engineers must know how much energy must be transferred.

Without a realistic heat duty:

- equipment sizing becomes arbitrary,

- utilities are misjudged,

- safety margins are guessed rather than defined.

Heat duty defines the minimum required thermal capability.

Heat Duty Is Tied to Process Behavior

Heat duty is not independent of the process.

It depends on:

- mass flow rate,

- composition,

- phase changes,

- reaction extent,

- operating temperature.

Examples:

- a reactor generates more heat at higher conversion,

- a distillation column requires more reboiler duty at higher reflux,

- a condenser duty rises when feed temperature increases.

This means heat duty is process-dependent, not equipment-dependent.

Why Heat Duty Is Rarely a Single Number

In datasheets, heat duty is often listed as a single value.

In reality, heat duty varies.

It changes with:

- throughput,

- feed conditions,

- ambient temperature,

- fouling,

- operating mode.

For example:

- summer cooling duty is higher than winter,

- startup duty differs from steady state,

- turndown operation shifts duty distribution.

Treating heat duty as fixed hides these variations and creates fragile designs.

Heat Duty vs Available Heat Transfer Capacity

One of the most common misunderstandings is assuming that calculated heat duty equals achievable heat transfer.

In practice:

- required heat duty may exceed what equipment can deliver,

- capacity depends on temperature driving force,

- fouling and flow conditions reduce effectiveness.

Meeting heat duty requires:

- sufficient temperature difference,

- adequate surface area,

- effective convection,

- manageable resistance.

Heat duty is a requirement.

Heat transfer capacity is a capability.

Confusing the two leads to chronic bottlenecks.

Why Equipment Can “Meet Duty” but Still Perform Poorly

Plants often report that equipment “meets duty” but still behaves badly.

This happens when:

- average heat duty is met,

- local heat transfer is insufficient,

- temperature profiles are unfavorable.

Examples:

- exchangers meet total duty but suffer hot spots,

- reactors remove average heat but develop local overheating,

- furnaces deliver duty but exceed tube metal limits.

Heat duty alone does not guarantee safe or stable operation.

Heat Duty During Startup and Shutdown

Heat duty during transient operation is often underestimated.

During startup:

- metal absorbs heat,

- process mass warms gradually,

- heat duty is higher than steady state.

During shutdown:

- stored energy must be removed,

- cooling duty persists after flow stops.

Ignoring transient heat duty leads to:

- aggressive startups,

- thermal shock,

- delayed stabilization.

Practical heat duty includes time-dependent effects, not just steady operation.

Utility Heat Duty Is Not the Same as Process Heat Duty

Another frequent confusion is equating process heat duty with utility demand.

In reality:

- utility duty depends on temperature approach,

- losses increase required utility flow,

- fouling raises utility consumption.

For example:

- a 10 MW process duty may require 12 MW of steam,

- cooling water flow increases as approach temperature shrinks,

- air coolers require more fan power at higher duty.

Utility systems feel the consequences of heat duty variation most strongly.

Why Heat Duty Drives Energy Cost

From an operating standpoint, heat duty translates directly into energy consumption.

Higher heat duty means:

- more fuel,

- more steam,

- more cooling water,

- higher electricity usage.

Because heat duty varies with process conditions, energy cost varies even when production rate appears constant.

Understanding this link helps explain:

- rising energy bills,

- seasonal cost changes,

- efficiency drift over time.

Heat Duty and Fouling

Fouling increases resistance.

As resistance increases:

- more temperature difference is required,

- utility flow rises,

- effective heat duty becomes harder to meet.

Plants often respond by:

- increasing utility supply,

- accepting higher operating temperatures.

This masks the real issue and accelerates degradation.

Heat duty management must include fouling awareness.

Owner Perspective: Heat Duty as a Business Variable

From an ownership viewpoint, heat duty affects:

- operating cost,

- achievable throughput,

- maintenance frequency,

- asset life.

Overestimating allowable heat duty:

- shortens equipment life,

- increases failure risk.

Underestimating required heat duty:

- limits production,

- wastes capital.

Balanced understanding protects both profit and reliability.

Final Perspective

Heat duty is not just a number in a datasheet.

It is a statement of:

- required energy movement,

- process demand,

- operating expectation.

Treating it as a fixed value simplifies paperwork but complicates operation.

Understanding its practical meaning allows plants to:

- design realistically,

- operate confidently,

- manage energy intelligently.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is fundamental plant awareness.

And it is essential for reliable, efficient process operation.

Understanding heat duty clarifies how much heat must be transferred, but it does not explain how temperature actually varies inside real equipment.

The next article in this sequence will examine how temperature gradients form along flow paths and across metal walls, and why these profiles matter for both performance and mechanical integrity.

Temperature Profiles in Equipment will be published soon. It will explain how temperature distributes through exchangers, vessels, and piping, and why equipment rarely operates at a single uniform temperature.

Until that article is available, you can continue with the next main article in this heat transfer series:

LMTD & Temperature Driving Forces Explained

This article explains how temperature difference acts as the true driving force for heat transfer and why engineers rely on LMTD rather than simple inlet–outlet ΔT in real exchanger design.