This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants series, which explains how heat transfer behavior translates into real equipment performance and long-term plant operation.

It follows the earlier discussion of the overall heat transfer coefficient in:

Overall Heat Transfer Coefficient (U) — Meaning, Reality & Plant Behavior

.

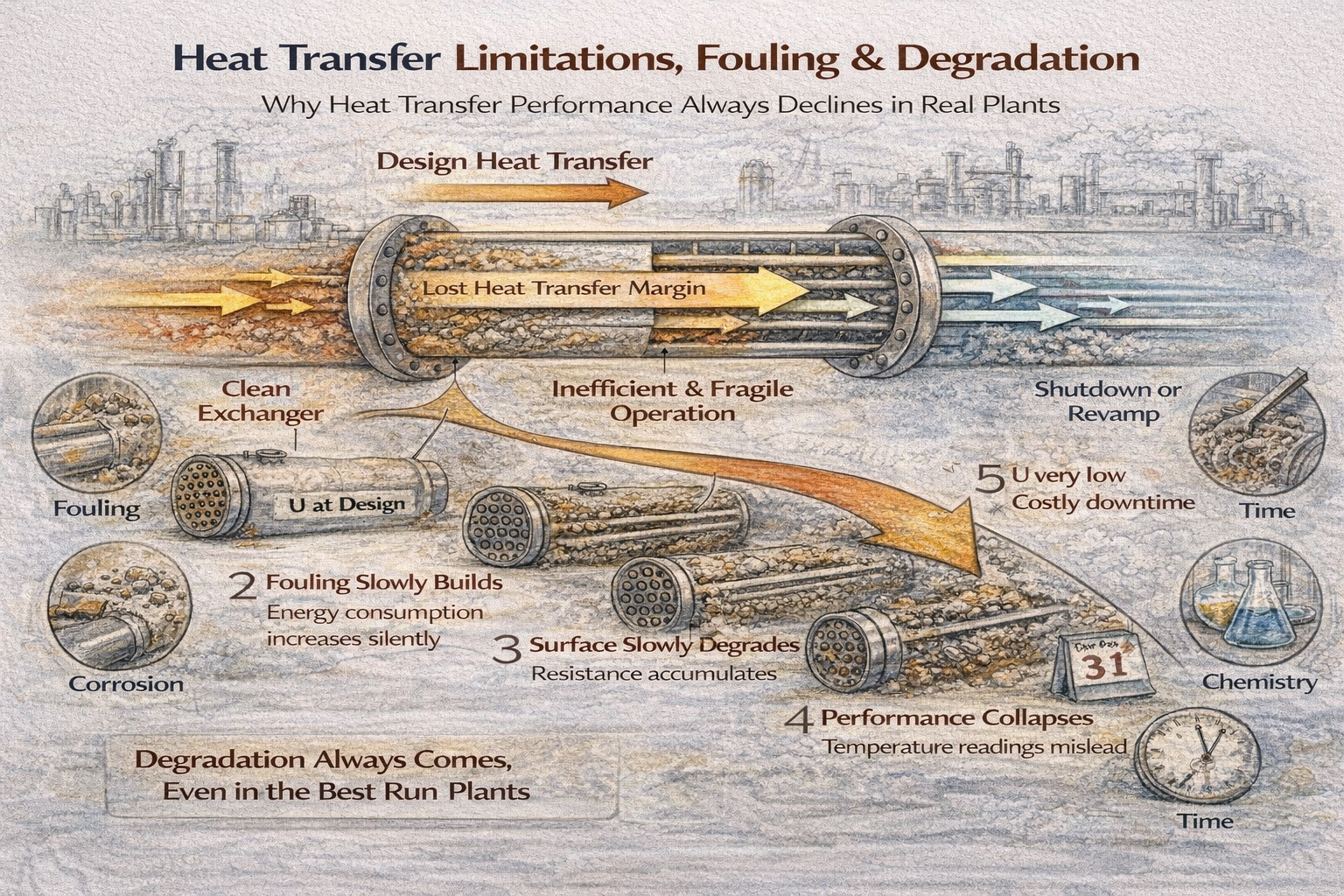

Building on that foundation, this article focuses on how fouling and degradation impose practical heat-transfer limitations over time, and why exchanger performance rarely remains at clean design conditions.

Why Heat Transfer Performance Always Declines in Real Plants

In textbooks, heat exchangers operate indefinitely at design conditions.

In real process plants, heat transfer performance always degrades.

Not occasionally.

Not unusually.

Always.

This degradation is not caused by poor design, careless operation, or bad maintenance alone. It is the natural outcome of:

- fluids flowing,

- surfaces interacting,

- chemistry evolving,

- time passing.

This article explains why heat transfer has unavoidable limitations, how fouling and degradation develop quietly, and why treating them as abnormal events leads to fragile designs, operational stress, and unnecessary cost.

Table of Contents

Heat Transfer Has Practical Limits, Not Just Theoretical Ones

In theory, heat transfer can always be increased by:

- adding area,

- increasing temperature difference,

- improving coefficients.

In practice, every plant operates within practical limits:

- pressure drop limits,

- temperature limits,

- metallurgy limits,

- control stability limits,

- economic limits.

Fouling and degradation push equipment toward these limits over time — even when nothing else changes.

Fouling Is Not a Failure — It Is a Process Reality

Fouling is often treated as a defect.

In reality, fouling is:

- a natural consequence of fluid–surface interaction,

- a time-dependent accumulation of resistance,

- unavoidable in most industrial services.

As soon as fluid flows:

- particles deposit,

- films form,

- crystals nucleate,

- polymers adhere,

- corrosion products settle.

Fouling begins immediately, even if performance loss is not yet visible.

Why Heat Transfer Degradation Is Usually Invisible at First

One of the most dangerous aspects of fouling is how quietly it develops.

Early fouling:

- adds small resistance,

- slightly increases required driving force,

- is easily masked by control action.

Operators compensate unconsciously:

- more steam,

- higher cooling water flow,

- tighter control.

Performance appears stable — while margin disappears.

By the time fouling becomes obvious, options are already limited.

Degradation Is Not Linear

Fouling and degradation do not progress at a constant rate.

Instead:

- early stages appear harmless,

- resistance accumulation accelerates,

- sensitivity to fouling increases,

- performance collapses suddenly.

This non-linear behavior explains why exchangers:

- work “fine” for long periods,

- then deteriorate rapidly,

- and seem to fail without warning.

The warning signs were present — but ignored.

Fouling Shrinks Driving Force Before It Reduces Duty

One common misconception is that fouling immediately reduces heat duty.

In reality:

- fouling first consumes temperature driving force,

- utilities compensate,

- duty is maintained.

Only when driving force margin is exhausted does duty fall.

This is why:

- energy consumption rises long before capacity drops,

- fouling problems are misdiagnosed as utility problems,

- operators feel pressure before production is affected.

Heat transfer fails from the margins inward, not from the center outward.

Why Designs That Ignore Degradation Are Fragile

Designs that assume:

- constant U,

- sustained clean surfaces,

- minimal fouling,

operate close to their limits from day one.

As fouling develops:

- no margin exists,

- control becomes aggressive,

- cleaning becomes urgent rather than economic.

These designs do not fail suddenly.

They age badly.

Robust designs assume degradation and remain operable anyway.

Fouling Is Often Mistaken for Poor Operation

When performance declines, the first response is often:

- “Increase flow”

- “Increase temperature”

- “Push utilities harder”

These actions:

- mask fouling,

- accelerate degradation,

- increase stress on equipment.

The plant appears responsive — while long-term damage increases.

Understanding fouling as a root cause prevents this cycle.

Heat Transfer Degradation Is a Life-Cycle Issue

Fouling and degradation must be understood across the entire equipment life:

- Design phase → margins and allowances

- Startup phase → rapid early fouling

- Normal operation → gradual resistance growth

- Late life → accelerated decline

- Revamp decisions → margin exhaustion

Treating fouling as a maintenance issue alone ignores its strategic importance.

Why Fouling Cannot Be Eliminated — Only Managed

No realistic plant eliminates fouling completely.

Even with:

- chemical treatment,

- filtration,

- surface coatings,

- optimized velocity,

fouling still occurs.

The real engineering challenge is not elimination.

It is managing the rate and impact of fouling.

Good plants:

- expect fouling,

- design for it,

- operate around it,

- clean based on economics — not panic.

Degradation Is Not Only Fouling

Heat transfer degradation also includes:

- corrosion thinning,

- surface roughening,

- erosion,

- deformation,

- gasket aging,

- baffle damage,

- flow maldistribution growth.

These effects:

- change resistance distribution,

- alter temperature profiles,

- increase fouling tendency further.

Degradation compounds itself over time.

Why Operators and Designers See Different Problems

Designers often see fouling as a calculated allowance.

Operators experience it as:

- rising utility demand,

- narrowing control margins,

- unstable temperatures,

- frequent interventions.

Both are correct — but incomplete alone.

Effective heat transfer management requires alignment between design intent and operating reality.

Owner Perspective: Fouling Is an Economic Variable

From an ownership standpoint, fouling affects:

- energy consumption,

- cleaning frequency,

- production availability,

- maintenance cost,

- equipment life.

Ignoring fouling does not save money.

It defers cost — usually with interest.

Managing fouling strategically improves:

- reliability,

- predictability,

- lifecycle economics.

Final Perspective

Heat transfer equipment does not fail because fouling exists.

It fails because fouling was:

- underestimated,

- ignored,

- postponed,

- or misunderstood.

Plants that accept fouling as inevitable:

- design with margin,

- operate calmly,

- clean deliberately,

- spend less over time.

Plants that fight fouling reactively:

- chase performance,

- stress equipment,

- increase cost,

- shorten asset life.

Understanding heat transfer limitations, fouling, and degradation is not pessimism.

It is realism.

And realism is the foundation of reliable, economical process plant operation.

We have established how heat transfer performance degrades over time and why fouling and aging impose unavoidable limitations in real plant operation.

The next step is to understand the most commonly used design allowance for this degradation — and why it is often misunderstood in practice.

Fouling Factor – Practical Meaning

This article explains what the fouling factor actually represents, how it is applied in exchanger design, and why treating it as a fixed number often leads to unrealistic performance expectations in operating plants.