This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which examines how heat transfer mechanisms behave in real process

equipment.

It builds on the earlier discussion in:

Conduction Explained with Plant Examples

.

For the broader framework that this article fits into, see:

Conduction in Process Equipment

.

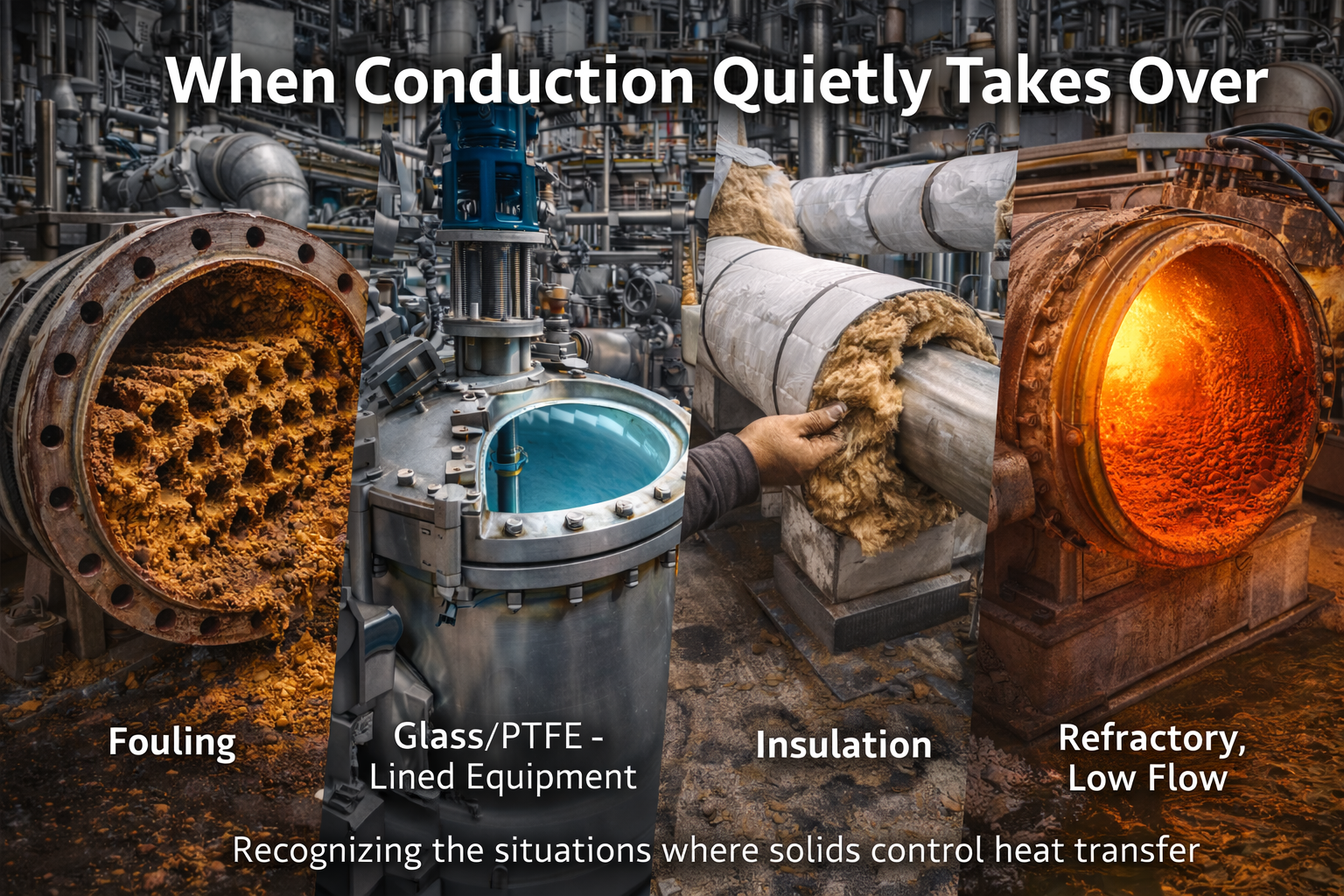

Conditions Where Solid Heat Transfer Controls Plant Behavior

In most operating equipment, heat transfer involves more than one mechanism. Convection, radiation, and conduction act together, with one usually playing a dominant role.

Because flowing fluids are visible and adjustable, convection often receives the most attention. Conduction, by contrast, is frequently treated as secondary.

In many real plant situations, this assumption is incorrect.

There are operating conditions where conduction through solid materials becomes the controlling heat transfer mechanism, governing temperature response, stability, and performance.

This article explains when and why that happens.

Table of Contents

Dominance Depends on the Weakest Link

Heat transfer behaves like a chain.

The overall rate is governed by the largest resistance in the path.

When convection resistance is small, conduction resistance can dominate.

When convection weakens, conduction often becomes the limiting step.

Recognizing which resistance controls the process at a given condition is essential for correct diagnosis and effective action.

Low or Zero Flow Conditions

One of the most common situations where conduction dominates is low flow or no flow.

Examples include:

- idle piping,

- standby vessels,

- blocked or isolated equipment,

- startup and shutdown phases.

When flow is low:

- convective heat transfer drops sharply,

- boundary layers thicken,

- temperature gradients flatten within fluids.

In these conditions, heat transfer continues primarily through solid walls by conduction.

This explains why:

- isolated systems still change temperature,

- heating or cooling appears slow,

- temperature equalization takes time.

Thick-Walled Equipment

Equipment with thick metal sections exhibits strong conduction effects.

Examples:

- high-pressure reactors,

- heavy-wall columns,

- large drums,

- exchanger tube sheets.

Thick walls:

- increase thermal resistance,

- store large amounts of thermal energy,

- slow temperature response.

In such equipment, even when fluid-side convection is strong, wall conduction controls the rate of heat movement.

This is why:

- temperature ramps must be limited,

- startups and shutdowns are time-consuming,

- thermal stress risk increases.

Stagnant Zones and Dead Pockets

Many pieces of equipment contain regions where fluid motion is weak or absent:

- corners of vessels,

- dead legs in piping,

- poorly mixed zones,

- bypassed internals.

In these zones:

- convection is minimal,

- temperature gradients within fluid are small,

- heat transfer relies on conduction through metal or stagnant fluid.

These regions often develop:

- cold spots,

- hot spots,

- condensation zones,

- corrosion issues.

Conduction dominates behavior in these areas.

Highly Insulated Systems

Insulation reduces heat loss to the environment, but it does not remove internal conduction.

In well-insulated systems:

- external convection and radiation are minimized,

- internal temperature gradients persist,

- heat redistributes through solids.

Examples include:

- hot oil systems,

- high-temperature reactors,

- insulated storage tanks.

In these cases, conduction within the equipment determines:

- internal temperature uniformity,

- cooldown rate,

- response to disturbances.

During Startup and Shutdown

Startup and shutdown are periods when conduction often dominates overall behavior.

During startup:

- hot fluids contact cold metal,

- convection initially transfers heat at the surface,

- conduction spreads heat through wall thickness.

During shutdown:

- hot metal releases stored energy,

- convection may be weak or absent,

- conduction governs cooldown.

Operational limits on heating and cooling rates are based primarily on conduction constraints, not convection.

When Fouling Reduces Convection Effectiveness

Fouling adds resistance on the fluid side.

As fouling builds:

- convective heat transfer weakens,

- temperature gradients increase,

- solid-side resistance becomes relatively more important.

In severely fouled equipment, conduction through the metal wall and fouling layer can dominate overall heat transfer behavior.

This explains why:

- increasing utility flow gives little benefit,

- cleaning restores performance suddenly,

- temperature approach worsens over time.

Small Equipment and Thin Flow Channels

In small-scale equipment or narrow channels:

- fluid volumes are small,

- surface-to-volume ratio is high,

- solids influence temperature strongly.

Examples include:

- small exchangers,

- instrument impulse lines,

- capillary systems.

In these cases, conduction through walls and supports can dominate temperature behavior, sometimes overriding process intent.

Cold Climate and Ambient-Dominated Conditions

In cold environments:

- external temperature differences are large,

- heat loss through walls and supports increases,

- conduction paths to ambient dominate.

Examples:

- outdoor piping in winter,

- exposed vessels,

- poorly insulated flanges.

Here, conduction to the environment governs temperature more than internal convection.

Why Increasing Flow Often Fails to Fix the Problem

A common operational response to poor heat transfer is increasing flow.

When conduction dominates:

- higher flow does not reduce solid resistance,

- temperature response remains slow,

- energy consumption increases without benefit.

This leads to frustration and misdiagnosis.

Recognizing conduction dominance avoids ineffective corrective actions.

Design Implications of Conduction-Dominated Conditions

Designers must account for conduction dominance when:

- selecting wall thickness,

- choosing materials,

- defining allowable temperature ramps,

- designing insulation and supports,

- planning startup procedures.

Ignoring conduction dominance often leads to:

- overly aggressive operating limits,

- premature equipment damage,

- conservative throughput restrictions later.

Maintenance Implications

Maintenance activities influence conduction behavior:

- insulation condition affects external heat loss,

- fouling alters internal resistance,

- repairs change metal continuity.

Understanding where conduction dominates helps prioritize:

- insulation repair,

- support redesign,

- dead-leg elimination,

- cleaning schedules.

Owner Perspective: Why Conduction Dominance Matters

From an ownership viewpoint, conduction-dominated conditions affect:

- startup time,

- energy consumption,

- reliability,

- equipment life.

Plants that understand these limits:

- plan realistic operating schedules,

- avoid unnecessary stress,

- reduce unplanned downtime.

Conduction dominance is not a defect.

It is a characteristic that must be managed.

Final Perspective

Conduction does not dominate all the time.

But when it does, it dictates how equipment responds, how fast temperatures change, and how much stress develops.

Ignoring conduction dominance leads to unrealistic expectations and repeated operational issues.

Recognizing it leads to better decisions, safer operation, and longer equipment life.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is practical plant awareness.

Once conduction becomes the controlling mechanism, the key question is no longer about flow or utilities — it is about how strongly the solid itself resists heat transfer.

The next article in this sequence will explain conduction in terms of thermal resistance, which is how engineers quantify and compare solid barriers in real equipment.

Thermal Resistance of Solids Explained will be published soon. It will clarify how thickness and conductivity combine to slow heat flow and why solids often set limits during startup, shutdown, and low-flow operation.

Until that article is available, you can continue with the next main article in this heat transfer series:

This article explains how fluid motion controls heat transfer in most operating equipment, why velocity and flow regime matter, and where engineers actually have leverage in plant thermal performance.