This article is Part 5 of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants series.

Start with the core foundation:

What Is Heat Transfer in Process Plants

.

For practical understanding:

Conduction Explained with Plant Examples

.

This article builds further by explaining:

When Conduction Dominates in Equipment

.

How Moving Fluids Control Heat Transfer in Real Plants

In process plants, most heat transfer problems are not caused by a lack of temperature difference or insufficient surface area. They are caused by how fluids move — or fail to move — inside equipment.

That movement determines convection, and convection controls how effectively heat is exchanged between fluids and equipment surfaces.

Understanding convection in process equipment is essential for explaining:

- why some equipment meets duty easily while others struggle,

- why performance changes with flow rate,

- why fouling and viscosity have such a strong impact,

- why startups and turndowns behave differently from steady operation.

This article explains convection from a real equipment perspective, not a textbook one.

Table of Contents

What Convection Means Inside Equipment

Convection is heat transfer that occurs when a fluid in motion carries energy.

In process equipment, this motion may be:

- forced by pumps or compressors,

- driven by gravity,

- induced by density differences,

- created by boiling or condensation.

Whenever a fluid flows over a surface, convection governs how heat moves between that surface and the fluid.

Unlike conduction, convection depends strongly on:

- velocity,

- flow pattern,

- fluid properties,

- surface condition.

This dependence makes convection the most variable — and most influential — heat transfer mechanism in operating plants.

Convection in Heat Exchangers

Heat exchangers are the clearest example of convection in action.

On both the hot and cold sides:

- fluids flow,

- boundary layers form,

- heat is transferred by convection.

Key observations from real plants:

- increasing flow rate often improves duty,

- fouling reduces performance quickly,

- maldistribution causes large efficiency losses.

In many exchangers, the limiting resistance lies on the fluid side, not in the metal wall.

This is why:

- exchanger performance is sensitive to operating conditions,

- cleaning restores duty without changing hardware,

- design margins erode over time.

Convection in Reactors

In reactors, convection determines how well heat is removed or supplied.

Examples include:

- jacketed reactors,

- internal coils,

- circulating loop reactors.

Convection governs:

- temperature uniformity,

- hot spot formation,

- response to heat generation.

Poor convection leads to:

- localized overheating,

- unstable temperature control,

- reduced selectivity.

In many cases, improving convection is more effective than increasing heat transfer area.

Convection in Distillation Columns

Distillation columns rely heavily on convection.

Heat input at the reboiler:

- generates vapor,

- drives internal circulation,

- establishes temperature gradients.

Heat removal at the condenser:

- controls reflux,

- stabilizes column pressure.

Inside the column:

- liquid and vapor convection governs tray or packing performance,

- maldistribution affects separation efficiency.

When convection weakens:

- columns flood or weep,

- energy consumption increases,

- product purity fluctuates.

Convection in Piping Systems

Piping is often overlooked as a heat transfer element.

In reality:

- flowing fluids convect heat to or from pipe walls,

- long lines exchange heat continuously with surroundings,

- flow regime affects heat loss rate.

Low flow or laminar conditions:

- reduce convection,

- increase temperature change along the line.

This explains:

- viscosity-related flow problems,

- unexpected temperature at downstream equipment,

- seasonal performance variation.

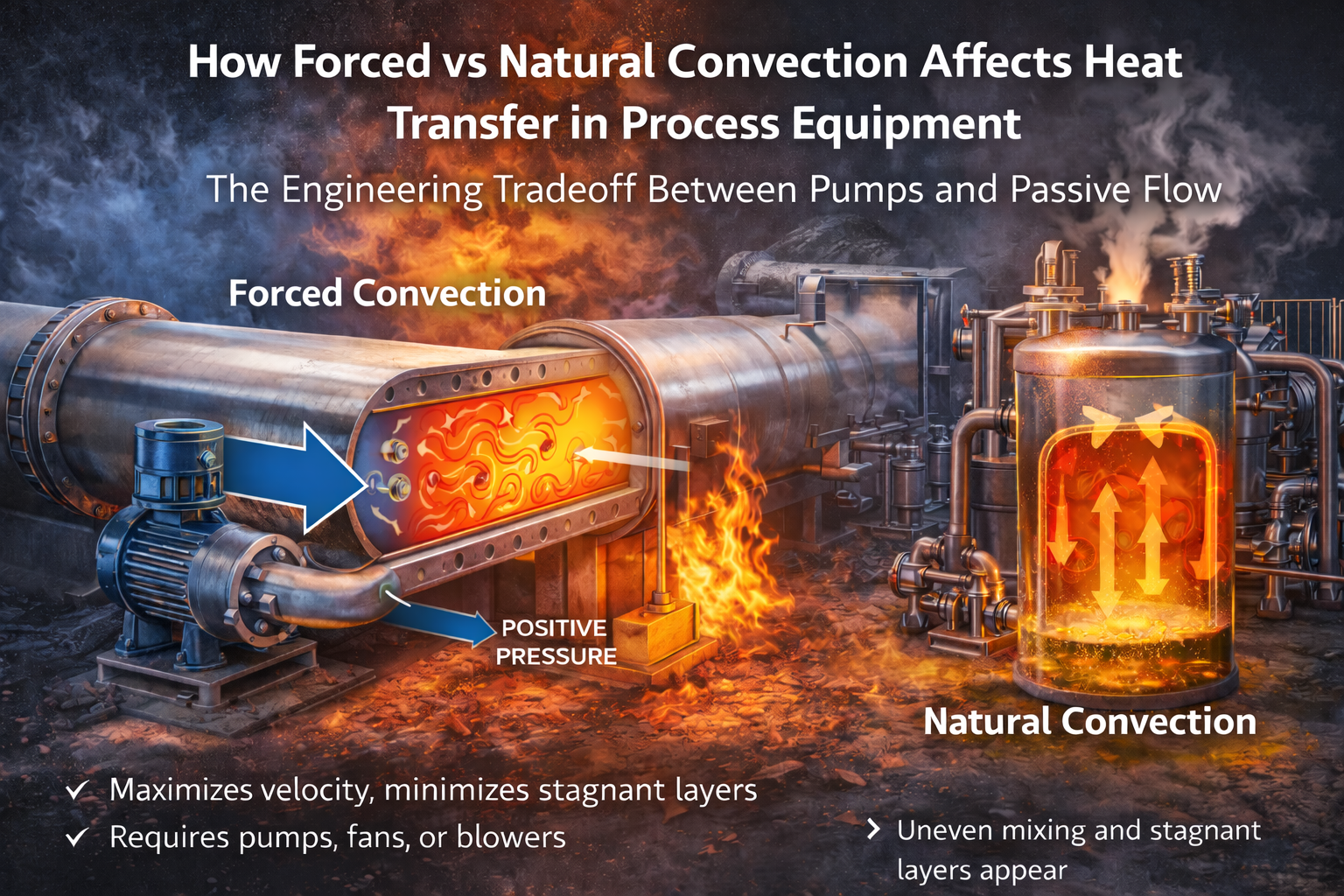

Natural Convection in Equipment

Not all convection requires pumps.

Natural convection occurs when:

- temperature differences create density differences,

- lighter fluid rises,

- heavier fluid falls.

Examples in plants:

- circulation in storage tanks,

- natural mixing in large vessels,

- heat loss from vertical surfaces.

Natural convection is weaker than forced convection, but it often dominates when flow is low or absent.

Ignoring it leads to incorrect assumptions about idle or standby equipment behavior.

Forced Convection and Its Sensitivity

Forced convection depends on:

- flow velocity,

- turbulence,

- geometry.

Small changes in flow rate can cause large changes in heat transfer rate.

This sensitivity explains why:

- turndown operation is challenging,

- pumps near minimum flow affect heat transfer,

- control loops become unstable at low rates.

Forced convection gives operators leverage — but also introduces risk if misunderstood.

Effect of Fluid Properties on Convection

Convection is highly sensitive to fluid properties.

Changes in:

- viscosity,

- density,

- phase,

- fouling tendency,

directly affect heat transfer.

Examples:

- cold viscous fluids heat slowly,

- fouled surfaces degrade convection,

- boiling enhances convection dramatically.

This sensitivity explains why identical equipment behaves differently with different services.

Convection During Startup and Shutdown

During startup and shutdown:

- flow rates change,

- convection strength varies,

- temperature gradients shift.

Early startup often involves weak convection, making equipment slow to heat.

Shutdown removes forced convection, leaving natural convection as the dominant mechanism.

Understanding this behavior helps prevent:

- thermal shock,

- uneven heating,

- excessive stress.

Why Convection Problems Are Often Misdiagnosed

Convection-related issues often appear as:

- control problems,

- equipment limitations,

- utility shortages.

In reality, the underlying cause is poor heat transfer due to:

- low flow,

- fouling,

- maldistribution,

- unfavorable fluid properties.

Without understanding convection, plants treat symptoms rather than causes.

Owner Perspective: Why Convection Drives Performance and Cost

From an ownership standpoint, convection influences:

- energy efficiency,

- throughput,

- maintenance frequency,

- reliability.

Improving convection often results in:

- lower utility consumption,

- more stable operation,

- extended equipment life.

These improvements come not from new equipment, but from better understanding and operation.

Final Perspective

Convection is where heat transfer becomes operational.

It links:

- design to operation,

- calculations to behavior,

- intention to reality.

Plants that understand convection:

- operate more smoothly,

- troubleshoot faster,

- consume less energy.

Plants that ignore it struggle with recurring, unexplained issues.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is everyday plant reality.

The next step is to distinguish different types of convection and

understand where each applies.

In the next article, we will explain:

Natural vs Forced Convection in Process Plants

This article explains how natural and forced convection differ in real

plant situations and why selecting the correct model matters in design

and operation.