This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants series.

It builds directly on the previous discussion in:

Conduction in Process Equipment

.

The Heat Transfer Mechanism That Actually Controls Daily Operation

In process plants, heat transfer is rarely limited by the availability of energy. It is limited by how effectively that energy can be carried away or delivered by fluids.

That mechanism is convection.

While conduction defines how heat moves through solid equipment, convection determines how heat is exchanged between solids and fluids, and how temperature changes propagate through the plant during normal operation.

This is why convection governs:

- most operating heat transfer rates,

- equipment performance under load,

- response to disturbances,

- capacity limits in real plants.

Understanding convection is essential for understanding how process plants actually behave during day-to-day operation.

Table of Contents

What Convection Means in Process Plants

Convection is heat transfer that occurs when a fluid in motion carries energy.

This motion may be:

- intentional (pumped flow),

- natural (buoyancy-driven),

- induced by phase change,

- driven by density differences.

In process plants, convection occurs whenever a fluid:

- flows through pipes,

- circulates inside vessels,

- passes through exchanger tubes,

- rises or falls due to temperature differences.

Unlike conduction, convection depends strongly on operating conditions.

Unlike radiation, it dominates at moderate temperatures.

Why Convection Is the Dominant Mechanism in Operating Plants

Most process equipment operates with fluids in motion.

Pumps, compressors, gravity flow, boiling, condensation — all create fluid movement. That movement continuously refreshes the fluid in contact with heat transfer surfaces.

This constant renewal allows heat to be:

- absorbed,

- transported,

- redistributed efficiently.

As a result:

- most heat exchangers are convection-limited,

- reactor temperature control depends on convection,

- utility systems rely almost entirely on convection.

Convection is not just present.

It is controlling.

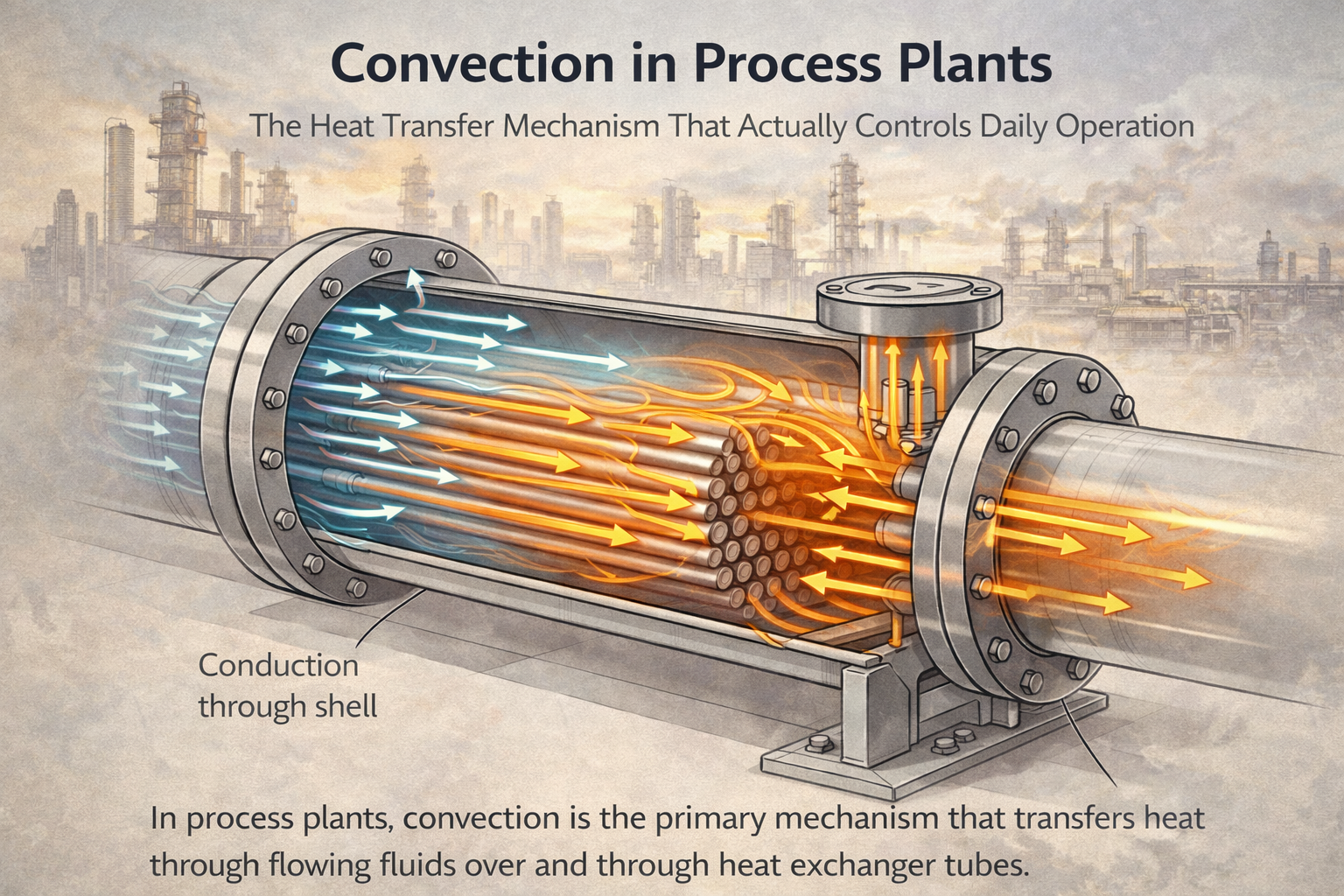

Convection as the Link Between Solids and Fluids

In real equipment, heat rarely moves directly from one fluid to another.

The typical path is:

- heat convects from hot fluid to a solid surface,

- heat conducts through the solid,

- heat convects from the solid to the cold fluid.

In this chain, convection often contributes the largest resistance.

This explains why:

- increasing fluid velocity improves heat transfer,

- fouling on the fluid side degrades performance quickly,

- cleaning restores exchanger duty dramatically.

Convection is where operating decisions have the most influence.

Why Flow Rate Matters So Much

Convection strength depends heavily on flow conditions.

Higher flow rates:

- thin the thermal boundary layer,

- increase turbulence,

- improve heat pickup or rejection.

Lower flow rates:

- thicken boundary layers,

- reduce heat transfer coefficient,

- increase sensitivity to fouling and viscosity changes.

This is why:

- exchangers underperform at turndown,

- reactors struggle at low circulation rates,

- startup and shutdown behave differently from steady state.

Flow does not create heat transfer.

It enables convection to use the available driving force.

Convection Explains Most Performance Drift

Plants often experience gradual performance loss rather than sudden failure.

Convection explains why.

Over time:

- fouling builds on fluid-side surfaces,

- effective flow area reduces,

- turbulence decreases,

- heat transfer coefficient drops.

As convection weakens:

- higher utility flow is required,

- approach temperatures increase,

- control margins shrink.

Temperature targets may still be met, but efficiency declines.

This slow degradation is characteristic of convection-controlled systems.

Natural and Forced Convection in Plants

Not all convection is driven by pumps.

Some convection occurs naturally due to density differences created by temperature gradients.

Examples include:

- circulation in storage tanks,

- natural draft in vertical vessels,

- buoyancy-driven flow in idle systems.

Other convection is forced by:

- pumps,

- compressors,

- agitators.

Both forms exist simultaneously in plants.

Which one dominates depends on geometry, temperature difference, and operating condition.

Understanding the difference is critical for:

- low-flow operation,

- standby conditions,

- safety analysis.

Why Convection Governs Temperature Uniformity

Uniform temperature distribution depends on effective mixing and convection.

Poor convection leads to:

- hot spots,

- cold zones,

- stratification,

- localized degradation.

This is particularly important in:

- reactors,

- large vessels,

- storage tanks,

- columns during turndown.

Convection determines not just average temperature, but temperature distribution.

Convection During Transients

Startup, shutdown, and disturbances expose convection limits clearly.

During these periods:

- flow rates change,

- density differences appear,

- circulation patterns shift.

Convection determines:

- how fast temperatures stabilize,

- how evenly heat spreads,

- where thermal stress develops.

Many transient issues attributed to “poor control” originate from convection limitations.

Why Convection Is Sensitive to Fluid Properties

Unlike conduction, convection depends strongly on fluid properties.

Changes in:

- viscosity,

- density,

- thermal conductivity,

- phase,

directly affect convection strength.

This explains why:

- cold viscous fluids heat slowly,

- fouling accelerates with temperature change,

- seasonal effects influence performance.

Convection links thermal behavior to process conditions.

Convection Sets Practical Capacity Limits

In many plants, throughput is not limited by equipment size, but by convection capability.

Examples include:

- maximum heat removal in reactors,

- condenser duty in columns,

- cooling water capacity,

- air cooler performance in summer.

When convection limits are reached:

- temperature control tightens,

- safety margins reduce,

- capacity cannot be increased without changes.

Recognizing convection limits prevents unrealistic debottlenecking attempts.

Owner Perspective: Why Convection Drives Cost

From an ownership standpoint, convection governs:

- energy efficiency,

- utility consumption,

- fouling rate,

- maintenance frequency.

Weak convection leads to:

- higher energy cost,

- reduced throughput,

- frequent cleaning,

- unstable operation.

Improvements that enhance convection often deliver immediate economic benefit.

Final Perspective

Convection is not a background phenomenon.

It is the mechanism that:

- carries heat through the plant,

- connects operating decisions to thermal response,

- determines whether equipment performs as intended.

Plants that understand convection:

- operate more predictably,

- control temperature more effectively,

- age more gracefully.

Plants that ignore it:

- fight recurring issues,

- consume more energy,

- accept unnecessary limitations.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is practical plant reality.

And it is essential for anyone responsible for process plant performance.

We have seen how convection governs heat transfer wherever fluids move in a process plant and why velocity, flow regime, and geometry matter more than most operators realize.

The next step is to examine how convection actually behaves inside real process equipment, where ideal assumptions often break down.

Convection in Process Equipment

This article explains how convection operates inside vessels, exchangers, piping, and stagnant zones, showing where fluid motion controls performance and where limitations quietly appear in real plant conditions.