This article is part of the

Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which explains how heat transfer governs behavior and performance

in real process equipment.

It builds on the earlier discussion of why heat transfer matters at the

plant level in:

Why Heat Transfer Governs Process Plant Behavior

.

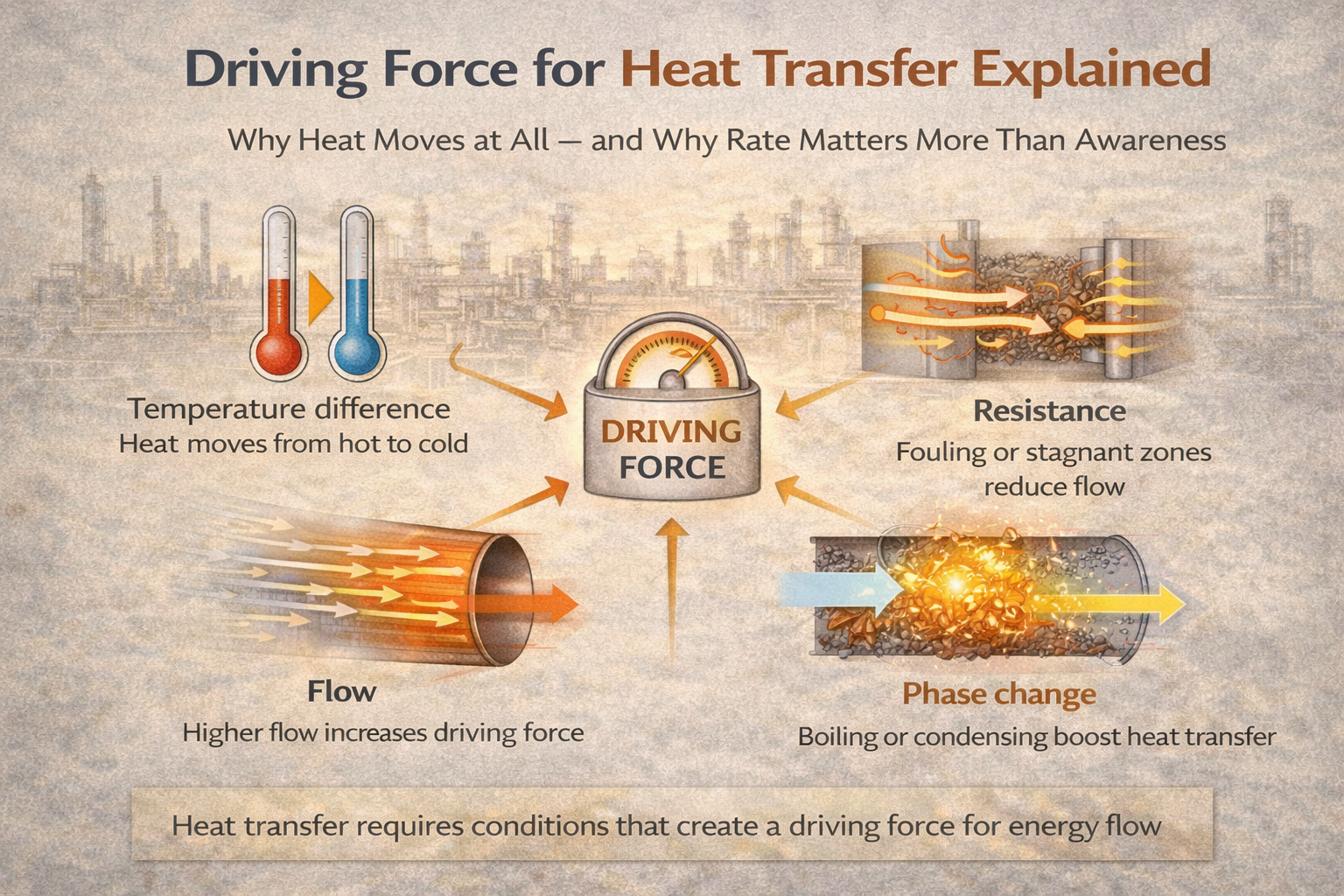

This article focuses on the concept of driving force — the fundamental reason

heat begins to move, and what ultimately controls the rate of transfer.

Why Heat Moves at All — and Why Rate Matters More Than Awareness

Heat transfer does not occur randomly.

It is driven.

In every process plant, heat moves because certain physical conditions exist. These conditions create a driving force — the reason heat starts moving and the reason it continues to move.

Understanding this driving force is essential. Without it, heat transfer calculations feel abstract, operating limits feel arbitrary, and troubleshooting becomes reactive.

This article explains what truly drives heat transfer in real plants, how that driving force changes during operation, and why plant behavior depends more on how strong the driving force is than on whether heat transfer equipment exists.

Table of Contents

Heat Transfer Needs a Reason, Not an Instruction

Heat does not require:

- operator action,

- control logic,

- rotating equipment,

- or design intent.

It requires only one thing:

a difference in thermal state.

Whenever such a difference exists, heat will move.

The larger the difference, the stronger the drive.

This is not a design choice.

It is a physical outcome.

Temperature Difference Is the Primary Driving Force

At its core, the driving force for heat transfer is temperature difference.

If one region is hotter than another, energy will move from the hotter region to the cooler one.

This applies to:

- fluid to fluid,

- fluid to metal,

- metal to ambient air,

- equipment to surroundings.

In process plants, temperature differences exist everywhere:

- between hot process streams and cooling water,

- between reactor contents and jackets,

- between pipelines and ambient air,

- between operating units and idle systems.

As long as this difference exists, heat transfer is unavoidable.

Why Direction Is Always the Same

Heat always flows from higher temperature to lower temperature.

This direction is not negotiable.

It cannot be reversed without external work.

This explains why:

- heating requires energy input,

- cooling happens naturally,

- insulation slows but does not reverse heat loss.

In plants, misunderstanding direction leads to poor expectations:

- assuming a stream can self-heat,

- expecting equilibrium without heat input,

- underestimating cooling requirements.

Direction is fixed.

Only the rate can be influenced.

Driving Force Is Not Just “Hot Minus Cold”

While temperature difference initiates heat transfer, effective driving force depends on more than just inlet temperatures.

In real plants, driving force is affected by:

- temperature profiles,

- phase changes,

- flow patterns,

- resistance layers,

- fouling buildup.

For example:

- a large inlet temperature difference may shrink rapidly along an exchanger,

- boiling or condensation may lock temperature at a phase boundary,

- fouling may block heat despite high temperature difference.

Understanding driving force requires looking beyond single numbers.

Resistance Determines How Much of the Driving Force Is Used

Heat transfer is opposed by resistance.

Resistance comes from:

- fluid films,

- metal walls,

- fouling layers,

- stagnant zones,

- insulation.

The actual heat transferred depends on the balance between:

- driving force (temperature difference),

- resistance (how hard it is for heat to move).

This explains why:

- increasing temperature does not always increase duty,

- higher utility flow sometimes shows diminishing returns,

- cleaning exchangers restores performance without changing temperatures.

Plants respond to effective driving force, not theoretical difference.

Why Flow Rate Influences Driving Force Effectiveness

Flow does not create temperature difference.

It determines how effectively that difference is used.

Higher flow rates:

- reduce boundary layer thickness,

- improve heat pickup or rejection,

- maintain temperature gradients.

Lower flow rates:

- allow local temperature equalization,

- reduce effective driving force,

- increase sensitivity to fouling.

This is why:

- exchangers underperform at turndown,

- batch heating slows near completion,

- startup behavior differs from steady operation.

The same temperature difference behaves differently at different flows.

Phase Change Strengthens the Driving Force

One of the strongest practical drivers of heat transfer is phase change.

During boiling or condensation:

- temperature remains nearly constant,

- large amounts of energy transfer occur,

- effective driving force is sustained over the surface.

This is why:

- condensers are compact yet powerful,

- reboilers dominate column behavior,

- small changes in pressure affect duty significantly.

Phase change locks temperature, preserving driving force and enabling high heat transfer rates.

Why Heat Transfer Slows Even When Temperature Looks Favorable

Operators often encounter situations where:

- temperature difference appears adequate,

- yet heat transfer is insufficient.

This usually occurs because:

- resistance has increased,

- driving force has degraded locally,

- heat paths have changed.

Common causes include:

- fouling layers,

- maldistribution,

- vapor blanketing,

- stagnant zones.

Temperature readings alone do not reveal these effects.

Understanding driving force explains why performance drops without obvious alarms.

Driving Force Changes Along Equipment Length

In most equipment, driving force is not constant.

Examples:

- in exchangers, temperatures approach each other,

- in reactors, heat generation varies spatially,

- in pipelines, heat loss accumulates gradually.

As driving force reduces:

- heat transfer rate drops,

- local limitations emerge,

- control response changes.

This explains why:

- exchangers meet duty initially but fail downstream,

- reactors develop hot spots,

- long pipelines show unexpected outlet temperatures.

Driving force must be evaluated as a profile, not a point.

Why Ambient Conditions Matter

Ambient temperature influences driving force wherever equipment interacts with surroundings.

This affects:

- storage tanks,

- exposed piping,

- air coolers,

- utilities.

Seasonal changes alter:

- available temperature difference,

- cooling effectiveness,

- heat loss rates.

Plants designed with narrow driving force margins experience seasonal instability.

Plants with adequate margins operate smoothly year-round.

Driving Force and Energy Cost Are Linked

Maintaining a driving force often requires energy.

Higher driving force means:

- higher steam pressure,

- colder cooling water,

- larger temperature gradients.

This increases energy consumption.

Efficient plants balance:

- sufficient driving force,

- minimal energy waste.

Overdesign wastes energy.

Underdesign limits capacity.

Driving force selection is an economic decision as much as a technical one.

Why Control Systems Cannot Create Driving Force

Control systems respond to deviation.

They do not create physical capability.

A controller can:

- open valves,

- increase utility flow,

- adjust setpoints.

It cannot:

- increase temperature difference beyond physical limits,

- remove resistance,

- reverse heat flow direction.

When driving force is insufficient, control becomes aggressive but ineffective.

Understanding this prevents misdiagnosis of “control problems” that are actually thermal limitations.

Owner Perspective: Driving Force as a Business Constraint

From an ownership viewpoint, driving force defines:

- achievable throughput,

- energy efficiency,

- flexibility during upsets,

- ability to operate in all seasons.

Plants with weak driving force:

- consume more utilities,

- hit limits early,

- struggle during disturbances.

Investments that restore or improve driving force often deliver:

- immediate operational benefits,

- long-term cost reduction.

Final Perspective

Heat transfer does not need encouragement.

It needs only a reason.

That reason is temperature difference, shaped by resistance, flow, and system design.

Plants behave the way they do because driving forces exist where engineers expect them — and often where they do not.

Understanding the driving force for heat transfer turns vague plant behavior into predictable response.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is the foundation of practical process engineering.

Understanding the driving force tells us what initiates heat transfer, but

it also raises a deeper question.

Why does heat move on its own at all, even without pumps, fans, or external

control?

The upcoming article, Why Heat Flows Spontaneously, explains

the physical reason heat always moves from hot to cold, how this connects to

equilibrium and entropy, and why the direction of heat flow is never a matter

of choice in real process equipment.