This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which examines how heat transfer mechanisms behave in real process

equipment.

It builds on the discussion of convection behavior in:

Convection in Process Equipment

.

For the broader framework of this topic, see:

Convection in Process Plants

.

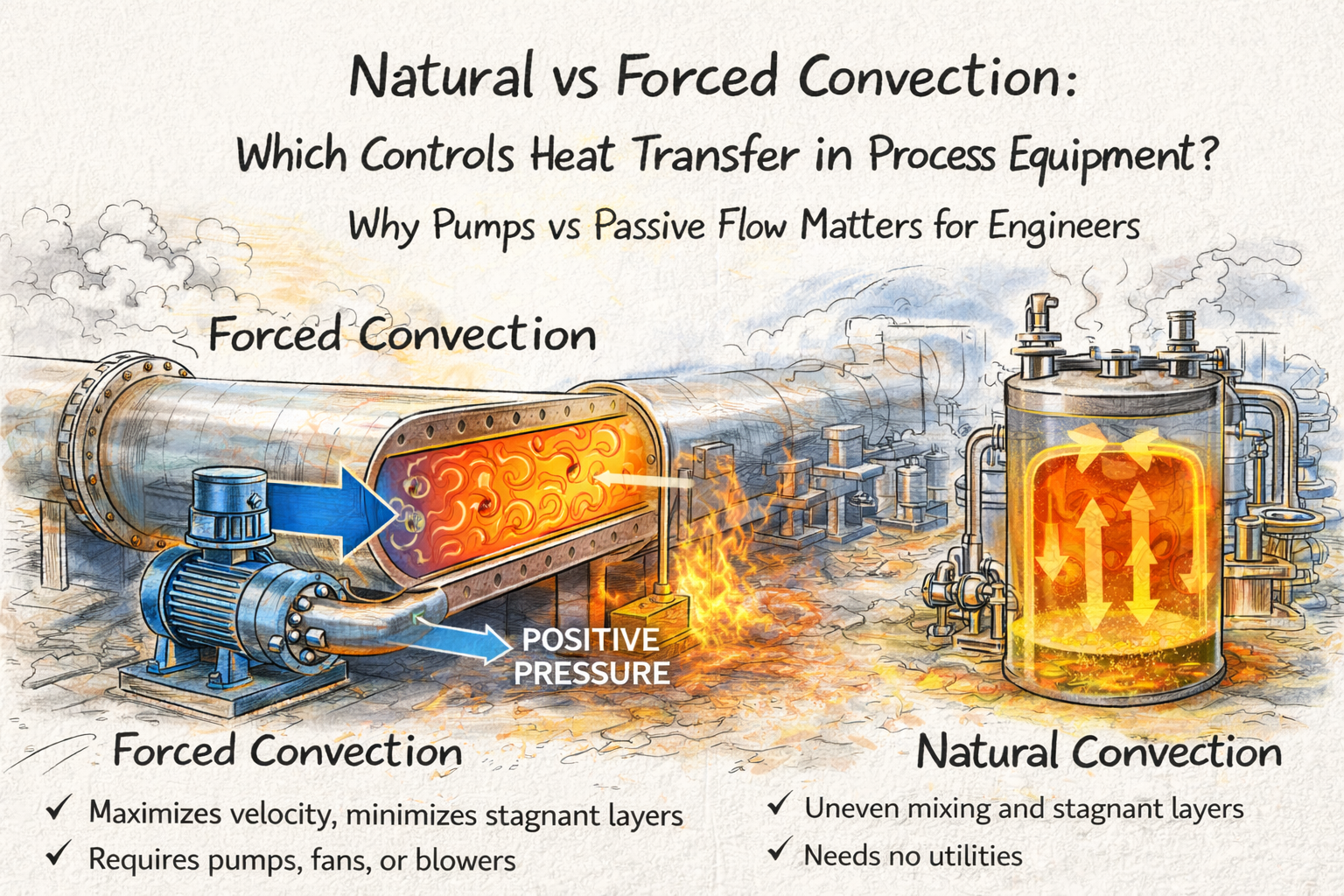

Two Ways Fluids Move Heat — and Why the Difference Matters in Plants

In process plants, convection is the primary mechanism by which heat is transferred between fluids and equipment surfaces. But convection does not occur in only one way.

There are two fundamentally different modes of convection:

- natural convection

- forced convection

Both exist in almost every plant.

Both influence equipment behavior.

But they behave very differently, respond to different factors, and dominate under different operating conditions.

Understanding the difference between natural and forced convection is essential for realistic design, operation, troubleshooting, and expectation-setting in real plants.

What Distinguishes Natural and Forced Convection

The distinction is not based on temperature or equipment type.

It is based on what causes the fluid to move.

- Natural convection occurs because of density differences created by temperature variation.

- Forced convection occurs because external energy forces the fluid to move.

The mechanism driving fluid motion determines how strong convection is, how controllable it is, and how predictable the resulting heat transfer will be.

Natural Convection: Heat Transfer Driven by Buoyancy

Natural convection occurs when a fluid moves because warmer portions become lighter and cooler portions become heavier.

This density difference creates circulation without pumps, fans, or agitators.

In process plants, natural convection occurs whenever:

- temperature gradients exist,

- fluid is free to move,

- no strong forced flow overrides buoyancy effects.

It is always present, even if unnoticed.

Common Plant Examples of Natural Convection

Natural convection plays a role in many everyday plant situations:

- circulation in storage tanks with temperature gradients

- heat loss from vertical vessels and columns

- warming or cooling of idle piping

- internal circulation in jacketed vessels at low agitation

- temperature equalization in shutdown equipment

These effects are slow but persistent.

They explain why “idle” equipment rarely remains thermally static.

Characteristics of Natural Convection

Natural convection is characterized by:

- low fluid velocities

- weak heat transfer coefficients

- strong dependence on geometry and orientation

- sensitivity to small temperature differences

Because the driving force is limited, natural convection:

- transfers heat slowly,

- produces large temperature gradients,

- responds poorly to control actions.

This makes it important during standby, shutdown, and low-flow conditions.

Forced Convection: Heat Transfer Driven by External Energy

Forced convection occurs when fluid motion is imposed by:

- pumps,

- compressors,

- fans,

- agitators,

- pressure differences.

This is the dominant mode of convection during normal plant operation.

Forced convection is responsible for:

- heat transfer in exchangers,

- jacket and coil performance,

- pipeline heat exchange,

- utility system effectiveness.

Because flow is imposed, forced convection is stronger, faster, and more controllable than natural convection.

Characteristics of Forced Convection

Forced convection typically shows:

- higher fluid velocities

- thinner thermal boundary layers

- higher heat transfer coefficients

- strong dependence on flow rate

Small changes in velocity can produce large changes in heat transfer rate.

This sensitivity gives operators leverage — and also creates risk if limits are misunderstood.

Why Forced Convection Dominates During Normal Operation

Most process equipment is designed to operate with continuous fluid movement.

As long as pumps and circulation systems are active:

- forced convection overwhelms natural convection,

- buoyancy effects become secondary,

- heat transfer is governed by flow conditions.

This is why:

- increasing flow often improves heat transfer,

- fouling becomes critical,

- viscosity changes strongly affect performance.

During normal operation, forced convection usually controls plant behavior.

When Natural Convection Becomes Important

Natural convection becomes important when forced flow is weak or absent.

Typical situations include:

- startup before full circulation is established

- shutdown after pumps stop

- turndown operation near minimum flow

- standby equipment with temperature differences

- emergency or abnormal conditions

In these cases:

- convection weakens dramatically,

- temperature changes slow,

- conduction and natural convection dominate.

Ignoring this transition often leads to incorrect expectations during transients.

Interaction Between Natural and Forced Convection

In many real situations, both modes coexist.

Examples:

- a reactor with agitation (forced) but buoyancy-driven stratification (natural)

- a storage tank with slow forced circulation and vertical temperature gradients

- a pipeline with low flow where buoyancy affects internal mixing

When forced convection weakens, natural convection shapes temperature distribution.

This interaction explains:

- stratification in vessels,

- uneven heating or cooling,

- delayed response to control actions.

Why Geometry and Orientation Matter

Natural convection is highly sensitive to geometry.

Vertical surfaces promote buoyancy-driven flow.

Horizontal surfaces behave differently depending on whether they are heated from above or below.

This explains why:

- vertical columns lose heat differently from horizontal vessels,

- upward-facing hot surfaces behave differently from downward-facing ones,

- equipment orientation affects standby behavior.

Forced convection is less sensitive to orientation but strongly dependent on flow path design.

Implications for Startup and Shutdown

During startup:

- forced convection starts weak,

- natural convection dominates initially,

- temperature gradients can be large.

During shutdown:

- forced convection disappears,

- natural convection remains,

- cooldown is slow and uneven.

Startup and shutdown procedures that assume forced convection throughout often underestimate thermal stress and stabilization time.

Why Natural Convection Cannot Be Ignored

Because natural convection is always present:

- it defines minimum heat transfer,

- it governs long-term equilibration,

- it explains slow temperature drift.

Designs that ignore natural convection:

- misjudge standby heat loss,

- underestimate warm-up times,

- misinterpret idle equipment behavior.

Natural convection may be weak, but it is persistent.

Owner Perspective: Why the Difference Affects Cost and Reliability

From an ownership standpoint:

- forced convection determines operating efficiency,

- natural convection determines standby losses and downtime behavior.

Poor understanding leads to:

- longer startups,

- higher energy use during holds,

- thermal damage during transitions.

Plants that account for both modes operate more predictably and economically.

Final Perspective

Natural and forced convection are not competing theories.

They are complementary realities.

Forced convection dominates when plants run.

Natural convection governs when they slow down or stop.

Understanding both — and knowing when one gives way to the other — is essential for realistic engineering judgment.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is practical plant awareness.

Distinguishing between natural and forced convection helps clarify how fluid motion changes the heat transfer mechanism in real plant equipment.

The next article in this sequence will take the next step: explaining why convection becomes the controlling mechanism in most operating process equipment.

Why Convection Controls Most Equipment will be published soon. It will explain why fluid-side behavior dominates exchanger performance and where engineers have the greatest leverage in practice.

Until that article is available, you can continue with the next main article in this heat transfer series:

Radiation Heat Transfer in Process Plants

This article explains when radiation becomes significant in plant equipment, why it dominates at high temperatures, and how engineers must account for it in fired heaters, furnaces, and thermal troubleshooting.