This article is part of the Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which explains how overall heat transfer performance is governed in

real process exchangers.

It builds directly on the earlier breakdown of how U is constructed in:

How U Is Built from Film + Wall + Fouling Resistances

.

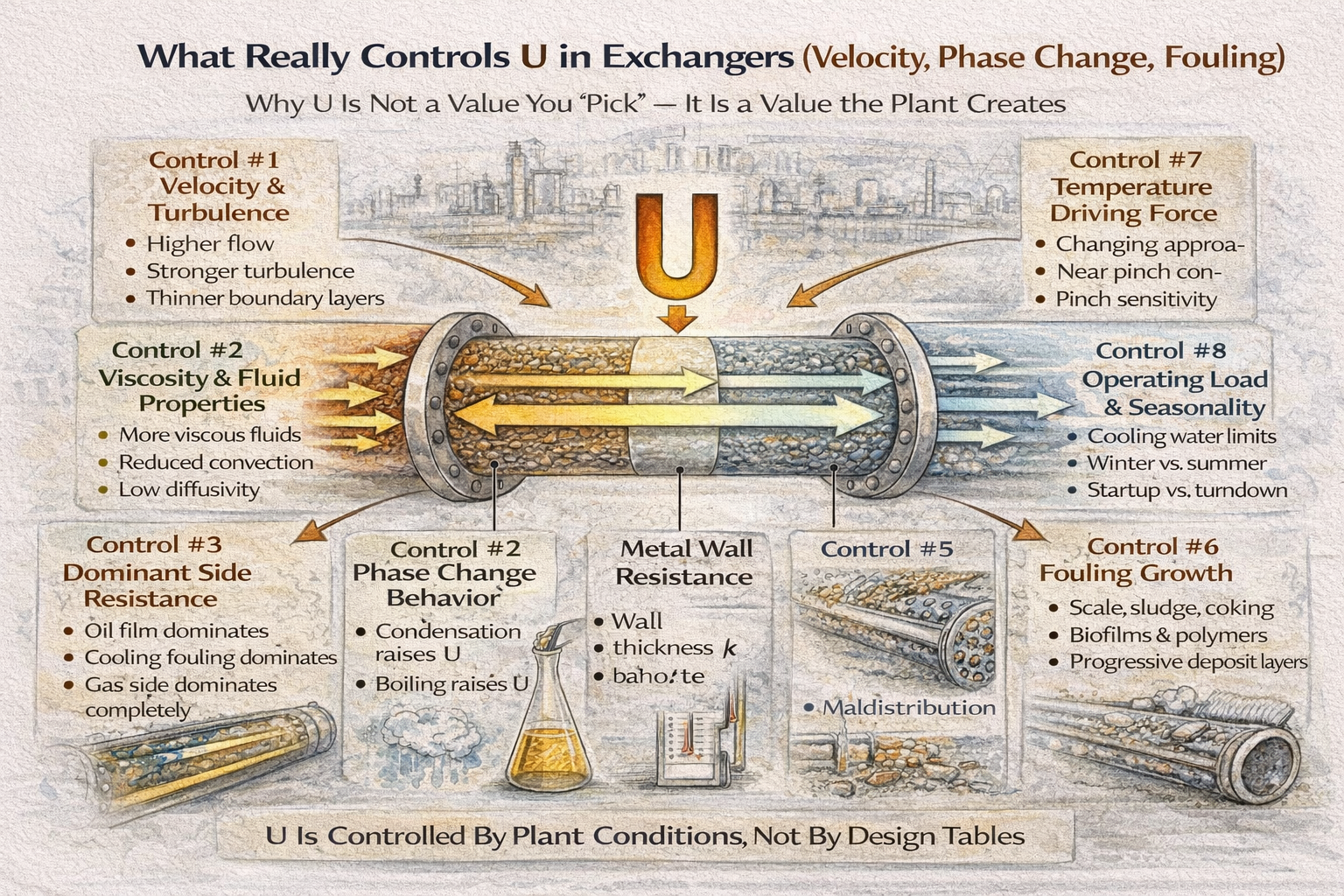

This article focuses on what actually controls U in practice — velocity,

phase-change behavior, and fouling — and where engineers have real leverage

during design and operation.

Why U Is Not a Value You “Pick” — It Is a Value the Plant Creates

The overall heat transfer coefficient U is often treated as if it comes from a table.

In design offices, it is common to hear:

- “Assume U = 300.”

- “This service should give a good U.”

- “Increase U and duty will improve.”

But real exchangers do not behave according to assumed numbers.

In real plants, U is controlled by a combination of factors that interact continuously:

- velocity and turbulence

- fluid properties and viscosity

- phase change behavior

- fouling growth over time

- maldistribution inside equipment

- operating load and seasonality

This article explains what truly controls U, why it changes so much, and why chasing U without understanding its drivers leads to repeated exchanger problems.

Table of Contents

Control #1: Fluid Velocity and Turbulence

The most powerful operational driver of U is velocity.

Heat transfer coefficients on each side depend strongly on turbulence.

Why turbulence matters

Near the wall, fluids form a boundary layer.

- In laminar flow, this layer is thick → resistance is high

- In turbulent flow, the layer is thin → resistance is low

So higher velocity usually increases turbulence, and turbulence usually increases U.

Plant reality

When plants operate below design load:

- flow drops

- turbulence weakens

- film resistance increases

- U falls sharply

This is why many exchangers perform worse at turndown than at full load.

But higher velocity is not always the solution

Increasing velocity may cause:

- excessive pressure drop

- tube vibration

- erosion

- accelerated fouling in some services

So velocity is a strong lever, but not a free one.

Control #2: Viscosity and Fluid Properties

U is not controlled only by flow rate.

It is also controlled by how the fluid behaves.

Viscous fluids resist convection.

Examples include:

- crude oil

- heavy hydrocarbons

- polymeric liquids

- syrups and resins

At low temperatures, viscosity increases sharply.

So exchangers heating viscous fluids often show:

- poor U at inlet

- better U near outlet

- uneven thermal performance

Key plant insight

A single “average U” hides large internal variation because fluid properties change with temperature.

Control #3: Which Side Dominates the Resistance

U is controlled by the largest resistance in the chain.

In some exchangers:

- hot-side oil film dominates

In others: - cold-side cooling water fouling dominates

In gas exchangers: - gas-side coefficient dominates completely

This explains why:

- improving one side may do nothing

- cleaning the wrong side gives little recovery

- adding area helps more than chasing coefficients

Understanding “which side controls” is more important than calculating U precisely.

Control #4: Phase Change Behavior

Phase change services often produce very high heat transfer coefficients.

Condensation

When steam condenses:

- temperature stays nearly constant

- latent heat transfer is large

- film coefficients are high

Condensers can show very high U compared to liquid-liquid exchangers.

Boiling

Boiling can also increase U — but only under stable regimes.

At high heat flux:

- vapor blanketing

- dry-out

- unstable boiling zones

can reduce effective heat transfer.

Practical takeaway

Phase change does not guarantee high U.

It produces high U only when hydrodynamics remain stable.

Control #5: Fouling — The Long-Term Controller of U

Fouling is the most persistent real-world controller of U.

Even if an exchanger has excellent clean performance:

- deposits add resistance

- U declines gradually

- driving force margin shrinks

Fouling is inevitable in most process services:

- scaling

- sludge deposition

- polymer films

- biological growth

- corrosion product redeposition

Plant reality

Exchangers do not operate at clean U.

They operate somewhere between:

- “less fouled” after cleaning

and - “highly fouled” before shutdown

So U in plants is a moving target.

Control #6: Maldistribution and Bypassing

Design assumes uniform flow distribution.

Real exchangers rarely deliver it.

Inside shell-and-tube exchangers:

- some tubes carry more flow

- some areas stagnate

- bypassing occurs near shell walls

- baffles leak

This creates:

- unused surface area

- localized fouling hot spots

- early pinch behavior

So the exchanger may have plenty of installed area, but only part of it is thermally active.

This is why:

- calculated U looks fine

- real performance remains poor

Control #7: Temperature Driving Force Interaction

U is often treated separately from driving force.

In reality, they interact.

As fouling develops:

- U drops

- more ΔT is required

- approach temperatures tighten

- pinch conditions appear

Near pinch, even small U degradation causes large duty loss.

So exchangers close to tight temperature approaches are extremely sensitive.

Robust exchangers are designed with driving force margin, not just U assumptions.

Control #8: Operating Load and Seasonal Conditions

U values measured in winter often differ from summer.

Why?

- cooling water temperature changes

- viscosity changes

- throughput changes

- utilities become constrained

So the same exchanger behaves differently across seasons.

This is why:

- summer is when exchangers “fail”

- winter hides thermal weakness

Plants that design only for nominal conditions often struggle at extremes.

Control #9: Aging, Surface Roughness, and Repeated Cleaning

Over years, exchanger surfaces change:

- corrosion roughens metal

- repeated cleaning damages oxide layers

- deposits become harder to remove

- baseline U declines permanently

Exchangers do not return to original “clean” condition after many cycles.

So U degradation is not only fouling.

It is lifecycle aging.

Why U Cannot Be Guaranteed

All these controls mean one thing:

U cannot be specified as a constant.

U emerges from:

- fluid behavior

- turbulence

- fouling history

- operating mode

- geometry imperfections

- time

So U is always a plant outcome, not a design promise.

Owner Perspective: What Controls U Controls Money

Owners feel U degradation as:

- rising steam consumption

- higher cooling water demand

- frequent cleaning outages

- throughput limitation

- unstable operation

Understanding what controls U helps plants spend money correctly:

- improving distribution rather than chasing velocity

- adding area rather than forcing turbulence

- optimizing cleaning rather than over-cleaning

U control is not academic.

It is economic.

Final Perspective

U is not controlled by one knob.

It is controlled by an interacting system of:

- velocity

- viscosity

- phase behavior

- fouling

- distribution

- operating history

Engineers who understand these controls stop asking:

- “What is the correct U value?”

And start asking:

- “What is controlling U in this exchanger right now?”

That shift is the difference between textbook heat transfer and plant heat transfer.

Once we understand what actually controls U — velocity, phase change, and

fouling behavior — it becomes clear that exchanger performance is highly

plant-specific.

This leads directly to an important question: why do textbook U values so

often fail when applied to real operating equipment?

The upcoming article, Why U Values from Books Fail in Plants,

explains why published U ranges rarely match site conditions, how fouling,

maldistribution, and aging distort performance, and why experienced engineers

treat book values as rough starting points rather than design truth.