This article is part of the

Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which examines how different heat transfer mechanisms influence

real process equipment and operating behavior.

It follows the earlier discussion focused on fired equipment in:

Radiation Heat Transfer in Furnaces

.

For the broader framework of radiation heat transfer in process plants,

see:

Radiation Heat Transfer in Process Plants

.

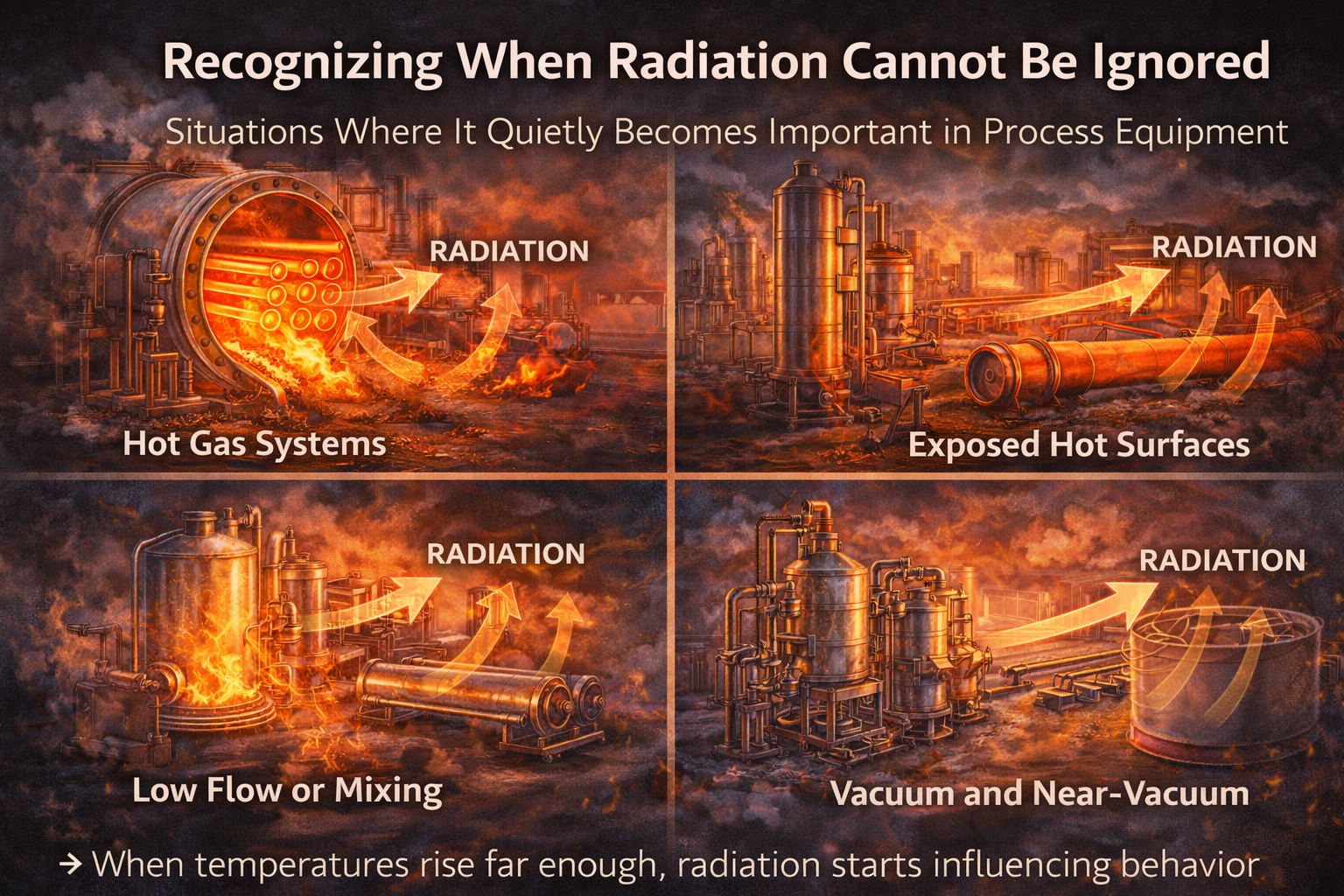

The Conditions Where Radiation Becomes the Controlling Heat Transfer Mode

In many process plants, radiation heat transfer is present but small. Under these conditions, conduction and convection dominate behavior, and radiation can be treated as a secondary effect.

However, there are specific conditions where radiation cannot be ignored.

When these conditions exist, radiation is no longer a correction term or safety margin. It becomes a governing mechanism that defines equipment limits, operating safety, and long-term reliability.

This article explains when radiation must be taken seriously, why it suddenly becomes dominant, and what happens when it is underestimated.

Table of Contents

Radiation Is Always Present — But Not Always Important

All surfaces emit radiant energy.

This is a physical fact.

At low and moderate temperatures:

- radiation heat flux is small,

- convection and conduction dominate,

- radiation effects blend into background losses.

At higher temperatures:

- radiation increases rapidly,

- small temperature changes produce large heat flux changes,

- radiation can exceed convection by a wide margin.

The transition from “negligible” to “dominant” is what often surprises plants.

High Surface Temperature: The Primary Trigger

The most important condition where radiation cannot be ignored is high surface temperature.

As surface temperature increases:

- radiant emission rises very rapidly,

- heat loss grows non-linearly,

- nearby surfaces absorb significant energy.

In practice, radiation becomes important when:

- metal or refractory surfaces are visibly hot,

- insulation skin temperatures rise noticeably,

- equipment radiates heat that can be felt at a distance.

At this point, radiation is no longer secondary.

Fired Equipment and Hot Process Units

Radiation must always be considered in:

- furnaces,

- fired heaters,

- incinerators,

- reformers,

- thermal oxidizers.

In these units:

- radiation dominates heat transfer,

- tube metal temperature is radiation-controlled,

- geometry and emissivity strongly affect performance.

Ignoring radiation in these systems leads directly to:

- overheated tubes,

- refractory damage,

- shortened equipment life.

In fired equipment, radiation is unavoidable and central.

Uninsulated or Poorly Insulated Hot Equipment

Radiation becomes critical whenever hot equipment surfaces are exposed.

Examples include:

- uninsulated piping,

- valve bodies,

- flanges,

- manways,

- inspection ports.

Even small exposed areas can radiate significant heat at high temperature.

Consequences include:

- high heat loss,

- unsafe surface temperatures,

- damage to nearby equipment,

- increased ambient temperature in operating areas.

In such cases, convection and conduction do not explain observed heat loss — radiation does.

Large Exposed Surface Area at Moderate Temperature

Radiation is not only about extreme temperature.

Large surface area can make radiation significant even at moderate temperatures.

Examples:

- large storage tanks,

- tall columns,

- extensive ducting,

- wide furnace casings.

Even if surface temperature is not extreme, the total radiated energy can be substantial.

This explains:

- high total heat loss from large vessels,

- elevated ambient temperatures near tall equipment,

- unexpected energy inefficiency.

Radiation scales with area as well as temperature.

Line-of-Sight Between Hot and Cold Surfaces

Radiation requires a clear line-of-sight.

Whenever:

- a hot surface directly “sees” a cooler surface,

- no shielding or insulation intervenes,

radiation heat transfer occurs.

This becomes critical when:

- hot equipment faces control panels,

- hot piping runs near cold vessels,

- furnaces are located near structural steel.

These effects cannot be explained by convection alone.

Radiation ignores airflow and travels directly across space.

High-Temperature Transients and Upsets

Radiation becomes especially important during transients.

During:

- startup,

- rapid firing changes,

- process upsets,

surface temperatures can change quickly.

Radiation responds instantly.

This leads to:

- sudden heat flux spikes,

- tube metal temperature overshoot,

- thermal stress beyond steady-state expectations.

Plants that design only for steady operation often experience radiation-driven damage during transients.

Radiation in Confined or Enclosed Spaces

Radiation cannot escape easily in enclosed spaces.

Examples:

- furnace enclosures,

- heater cabins,

- duct galleries,

- enclosed pipe racks.

In these environments:

- radiant energy reflects between surfaces,

- effective heat flux increases,

- ambient temperature rises.

This explains why:

- enclosed hot areas become extremely uncomfortable,

- insulation degradation accelerates,

- ventilation alone does not solve heat issues.

Radiation accumulates when space is confined.

When Personnel Safety Is Involved

Radiation must never be ignored when personnel exposure is possible.

High radiant heat flux can:

- cause burns without contact,

- overheat protective clothing,

- make work areas inaccessible.

This is why:

- surface temperature limits are specified,

- minimum safe distances are enforced,

- shielding is installed around hot equipment.

In safety analysis, radiation is often the controlling factor.

Radiation and Nearby Equipment Damage

Radiant heat does not stop at its intended target.

Nearby equipment exposed to radiation can experience:

- accelerated insulation aging,

- seal degradation,

- electrical component failure,

- structural weakening.

These failures often appear “mysterious” because convection calculations show no issue.

Radiation is the missing explanation.

Why Radiation Problems Appear Suddenly

Radiation-related problems often appear abruptly because:

- radiation increases rapidly with temperature,

- surface condition changes over time,

- insulation deteriorates gradually.

A small increase in operating temperature or a small insulation failure can push the system into a radiation-dominated regime.

This creates the illusion of sudden failure.

In reality, the system crossed a thermal threshold.

Why Radiation Is Often Underestimated

Radiation is underestimated because:

- it is invisible,

- it is harder to quantify,

- it depends on surface emissivity and geometry,

- it behaves non-linearly.

Designers often simplify radiation assumptions.

Operators rely on experience until limits are reached.

When those limits are crossed, radiation becomes unavoidable.

Owner Perspective: When Radiation Becomes a Cost and Risk Driver

From an ownership standpoint, radiation cannot be ignored when it affects:

- energy efficiency,

- equipment life,

- safety compliance,

- unplanned shutdown risk.

Radiation-related damage is often:

- expensive,

- sudden,

- safety-critical.

Managing radiation proactively:

- reduces long-term cost,

- improves reliability,

- protects personnel.

Final Perspective

Radiation is not always the dominant heat transfer mechanism.

But when certain conditions are met, it becomes the controlling one — regardless of design intent.

High temperature, exposed surfaces, line-of-sight, confined spaces, and transients all push systems into radiation-dominated behavior.

Recognizing these conditions early prevents:

- unsafe operation,

- unexpected damage,

- costly shutdowns.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is practical plant awareness.

And it is essential wherever high temperatures exist in process plants.

Recognizing where radiation dominates is only the first step. The next challenge is understanding why radiation is far more difficult to quantify than conduction or convection in real equipment.

The next article in this sequence will explain why radiation calculations depend heavily on geometry, surface behavior, and assumptions that rarely remain stable in plant conditions.

Why Radiation Is Hard to Calculate will be published soon. It will clarify the practical limitations of radiation models and why engineers often rely on judgment as much as equations.

Until that article is available, you can continue with the next main article in this heat transfer series:

How Heat Transfer Is Quantified in Process Plants

This article introduces the practical engineering quantities — duty, driving force, U values, and performance metrics — that connect heat transfer theory to real design and operating decisions.