This article is part of the

Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series.

The series explains how heat transfer behaves in real process equipment

and how practicing engineers turn that behavior into

quantitative tools for design and analysis.

If you are new to the series, start here:

What Is Heat Transfer in Process Plants

.

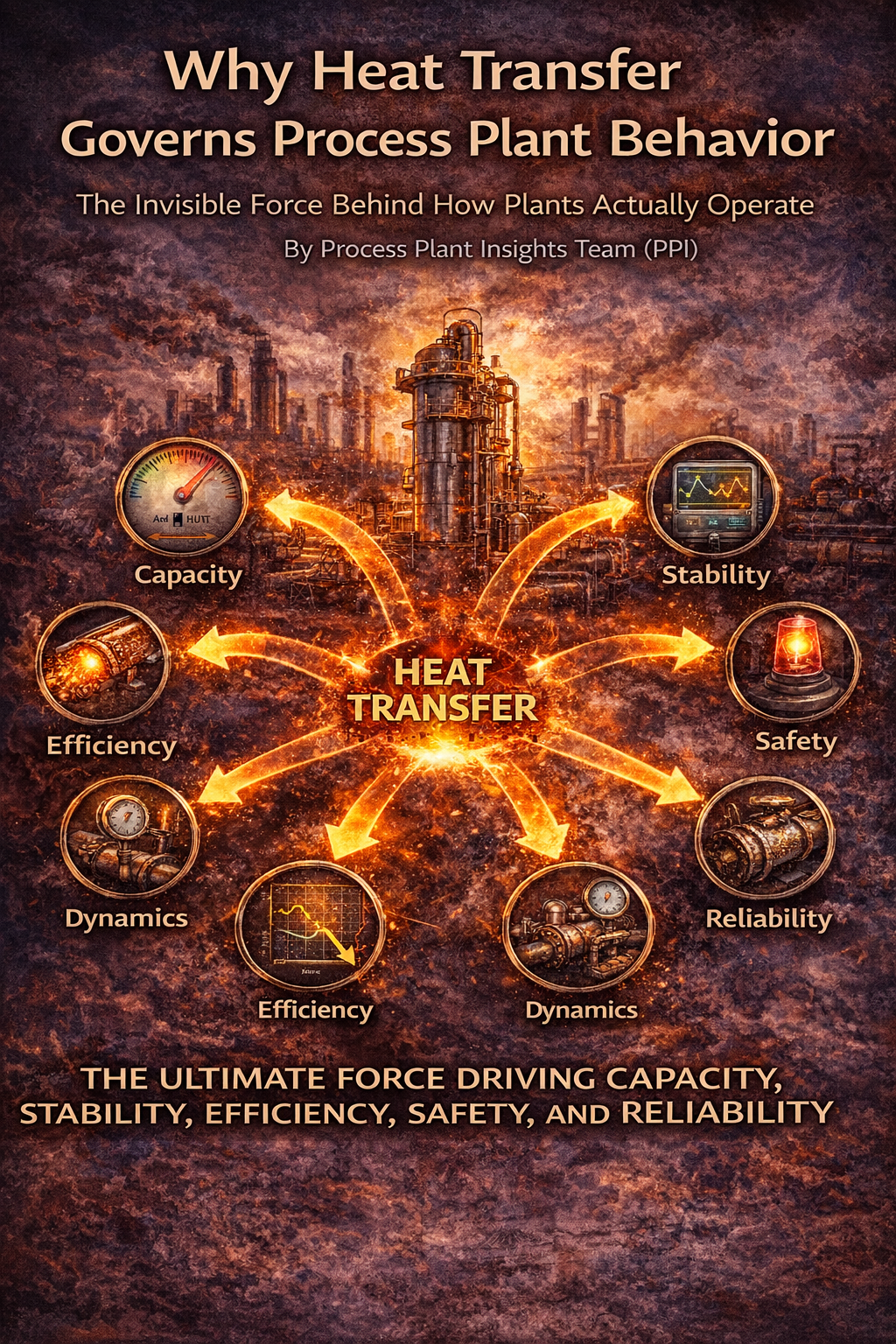

The Invisible Force Behind How Plants Actually Operate

Process plants appear to be controlled by equipment, instrumentation, and operating procedures. Pumps move fluids. Reactors convert materials. Columns separate products. Control systems maintain setpoints.

Yet beneath all visible activity lies a quieter influence that ultimately governs how plants behave: heat transfer.

Heat transfer does not announce itself.

It does not show up as a single alarm or failure.

But it continuously shapes capacity, stability, efficiency, safety, and long-term reliability.

Plants do not merely contain heat transfer.

They are governed by it.

Table of Contents

Governance Is Different from Presence

Many discussions about heat transfer focus on where it occurs: exchangers, heaters, condensers, jackets.

That is incomplete.

Heat transfer governs plant behavior because it:

- determines how fast systems respond,

- sets practical operating limits,

- defines stability margins,

- controls energy consumption,

- drives long-term degradation.

A governing factor does not need to be visible.

It only needs to be unavoidable and decisive.

Heat transfer meets both conditions.

Every Plant Is an Energy System First

At a fundamental level, a process plant is an energy management system.

Raw materials enter with one energy state.

Products leave with another.

Between those two points:

- energy is added,

- energy is removed,

- energy is redistributed,

- energy is lost.

Material conversion is impossible without energy movement.

Separation is impossible without energy gradients.

Even storage is influenced by energy exchange with surroundings.

Heat transfer is the dominant mechanism by which this energy movement occurs.

Why Plant Behavior Depends on Rates, Not Intentions

Design intent defines what should happen.

Plant behavior reflects what can happen.

The difference lies in rates.

Heat transfer rates determine:

- how quickly a reactor can remove reaction heat,

- how much vapor a reboiler can generate,

- how fast a product can be cooled,

- how much throughput utilities can support.

If the required heat transfer rate exceeds what the system can physically deliver, behavior changes:

- temperature drifts,

- control tightens,

- throughput caps,

- safety margins shrink.

No control strategy can override this limitation.

Heat Transfer Governs Dynamic Response

Plants are rarely steady for long.

They start up.

They shut down.

They change rates.

They respond to disturbances.

All dynamic behavior is governed by:

- how much heat is stored,

- how fast heat can move,

- how evenly heat is distributed.

Systems with high thermal inertia respond slowly.

Systems with low thermal resistance respond sharply.

This is why:

- large vessels take hours to stabilize,

- small systems overshoot easily,

- startups feel unpredictable,

- shutdowns require caution.

These behaviors are not operational failures.

They are thermal realities.

Temperature Control Is Not Thermal Control

Temperature is what operators see.

Heat transfer is what the process obeys.

A temperature loop may hold setpoint while:

- energy efficiency collapses,

- utilities are overstressed,

- fouling increases.

Conversely, temperature may fluctuate even when:

- overall heat balance is acceptable,

- safety margins remain intact.

Plants that focus only on temperature signals often misinterpret behavior.

Plants that understand heat transfer recognize patterns earlier and respond more effectively.

Why Capacity Is Usually a Thermal Limit

Mechanical equipment is often capable of more than it delivers.

Pumps can handle higher flow.

Columns can accept more vapor.

Reactors can process more feed.

Yet throughput stalls.

The limiting factor is often:

- heat removal in reactors,

- reboiler duty in columns,

- condenser capacity,

- cooling water approach temperatures,

- utility network limits.

These are not mechanical constraints.

They are heat transfer constraints.

Capacity expansion frequently means thermal expansion, not physical expansion.

Heat Transfer Governs Energy Efficiency

Energy efficiency is not defined by how much energy is added, but by how effectively it is transferred.

Losses occur when:

- temperature differences are larger than necessary,

- fouling increases resistance,

- insulation degrades,

- heat escapes unintentionally.

Over time:

- fuel consumption rises,

- cooling demand increases,

- operating cost escalates.

Because this degradation is gradual, it is often normalized.

Plants adapt to inefficiency instead of correcting it.

Thermal governance explains why energy costs rise even when production remains constant.

Aging Plants Age Thermally

Plants rarely fail because steel weakens first.

They fail because thermal margins disappear.

As plants age:

- fouling accumulates,

- surfaces roughen,

- flow distribution worsens,

- insulation effectiveness declines.

Each change increases thermal resistance.

The result is not immediate failure, but:

- reduced flexibility,

- tighter control,

- narrower safe operating windows.

Thermal aging explains why older plants feel “harder to run” even when equipment appears intact.

Utilities Are the Mirror of Thermal Health

Utility systems reflect the plant’s thermal condition.

Rising steam demand, warmer cooling water returns, overloaded hot oil systems — these are symptoms, not causes.

Utilities respond to:

- declining heat transfer effectiveness,

- increasing thermal resistance,

- growing energy losses.

When utilities reach limits, the entire plant follows.

This is why utility bottlenecks often define plant capacity long before process equipment does.

Safety Is Fundamentally Thermal

Many safety incidents have thermal roots:

- runaway reactions,

- overheating during startups,

- thermal stress failures,

- insulation breakdowns,

- unexpected vapor generation.

Even when the final event appears mechanical or procedural, the initiating condition is often uncontrolled heat accumulation or delayed heat removal.

Understanding heat transfer improves not only efficiency, but also predictability and safety.

Why Heat Transfer Governs Control Behavior

Control systems act on measurements.

Processes respond to physics.

When heat transfer is slow:

- controllers appear ineffective,

- operators intervene,

- oscillations develop.

When heat transfer improves suddenly:

- responses become aggressive,

- overshoot occurs,

- limits are breached.

Tuning alone cannot fix a thermally constrained process.

Stable control requires alignment between control action and thermal response.

Why This Understanding Changes Engineering Judgment

Engineers who recognize thermal governance:

- ask better questions,

- interpret trends correctly,

- avoid superficial fixes.

They look beyond:

- temperature numbers,

- immediate symptoms,

- short-term adjustments.

They examine:

- heat paths,

- resistances,

- margins,

- degradation mechanisms.

This perspective separates troubleshooting from guesswork.

Owner Perspective: Why Heat Transfer Governs Profitability

From an ownership standpoint, heat transfer governs:

- energy spend,

- achievable throughput,

- maintenance frequency,

- asset life,

- operational stability.

Poor thermal performance creates continuous cost.

Good thermal management delivers continuous value.

Few improvements influence so many aspects of profitability simultaneously.

Final Perspective

Heat transfer does not compete with process engineering.

It underpins it.

Plants do not fail because heat transfer exists.

They struggle because its influence is underestimated.

Once heat transfer is recognized as a governing force rather than a background calculation, plant behavior becomes more predictable, decisions become more grounded, and performance improves sustainably.

This understanding is not advanced theory.

It is practical reality.

And it is essential for anyone responsible for how a process plant truly operates.

We have established why heat transfer governs process plant behavior and why it must be treated as a controlling reality rather than a background effect.

The next article in this sequence will focus on what actually causes heat to move and what determines the rate at which it transfers in real equipment.

Driving Force for Heat Transfer Explained will be published soon. It will clarify the true physical drivers behind heat transfer and why temperature difference governs plant thermal behavior.

Until that article is available, you can continue with the next main article in this heat transfer series:

Conduction in Process Equipment

This article explains where conduction quietly dominates in process plants, why solids often control thermal behavior during startups and shutdowns, and how conduction effects are commonly underestimated.