This article is part of the

Heat Transfer in Process Plants

series, which explains how heat transfer behaves in real process equipment

and how that behavior is translated into engineering decisions.

It follows the earlier discussion on high-temperature heat transfer in:

Radiation Heat Transfer in Process Plants

.

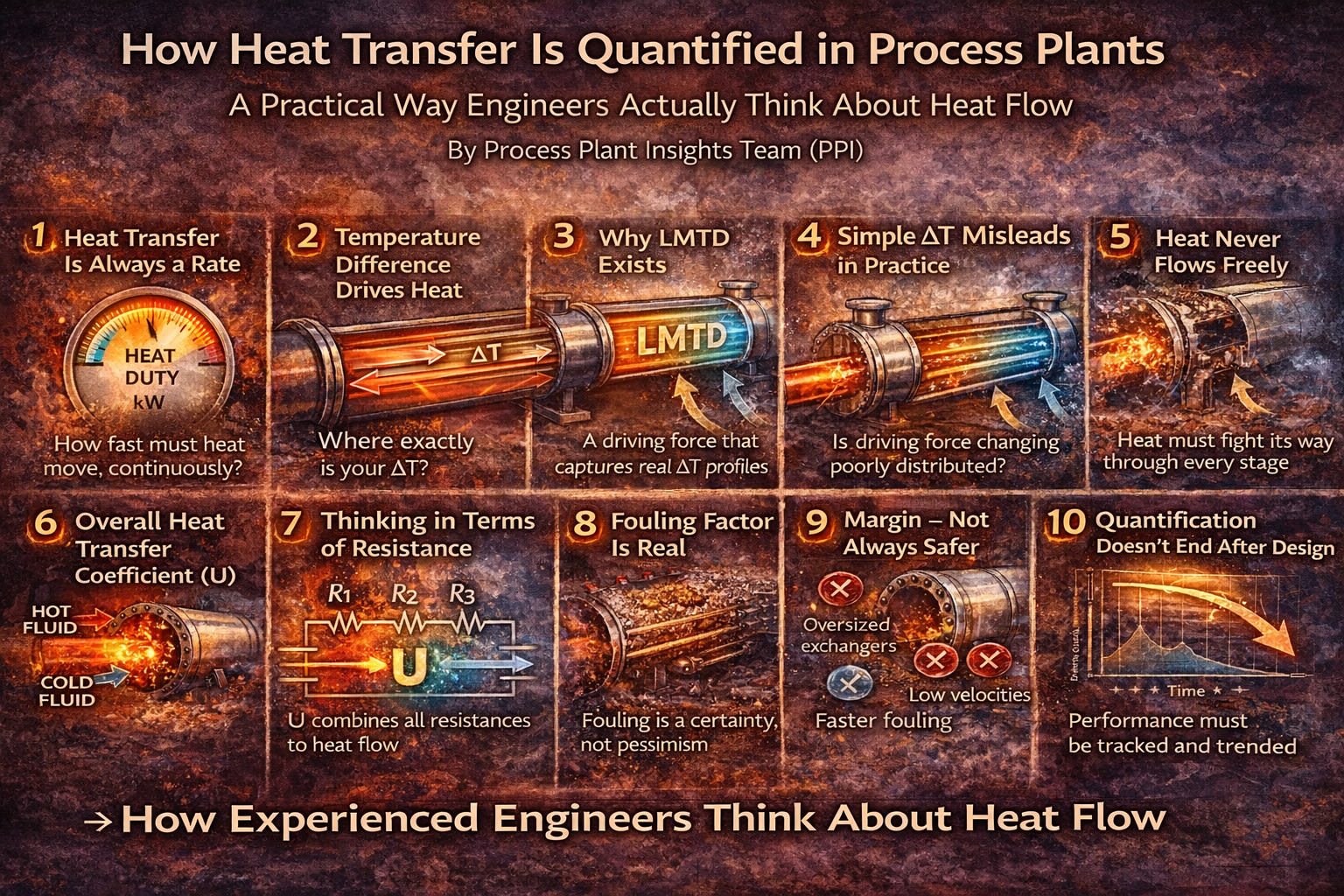

Building on those mechanisms, this article introduces how engineers

quantify heat transfer using measurable parameters and design tools.

Turning Physical Behavior into Engineering Decisions

Understanding that heat transfer occurs is only the beginning.

Every real engineering decision depends on how much heat is transferred, how fast, and where.

Process plants do not fail because heat transfer exists.

They struggle because heat transfer is misjudged, overestimated, or misunderstood when quantified.

This article explains how heat transfer is actually quantified in process plants — not as textbook equations, but as a structured way of thinking that connects physical behavior to design limits, operating decisions, safety margins, and cost.

Quantification Is About Capability, Not Calculation

In theory, heat transfer can be expressed with equations.

In practice, quantification answers more practical questions:

- Can the equipment remove the required heat?

- Will temperature stay within safe limits?

- How much utility is actually needed?

- What happens when conditions change?

Quantification is therefore not about mathematical precision.

It is about engineering confidence.

Plants do not need exact numbers.

They need reliable margins.

Table of Contents

Heat Transfer Is Always Spatial, Not Lumped

One of the biggest misconceptions in heat transfer quantification is treating equipment as if it has a single temperature.

In real plants:

- temperature varies along length,

- temperature varies across thickness,

- temperature varies with time.

Heat transfer is distributed, not lumped.

Quantification must respect this reality, or it becomes misleading.

The First Quantity Engineers Care About: Heat Duty

The starting point for quantification is heat duty.

Heat duty answers a simple question:

How much energy must be added or removed per unit time?

This determines:

- utility sizing,

- exchanger selection,

- firing rate,

- cooling system capacity.

Without a realistic heat duty, all downstream calculations are meaningless.

But heat duty itself is often misunderstood.

Why Heat Duty Is Not a Fixed Number

Heat duty is frequently treated as a constant.

In reality, heat duty:

- varies with throughput,

- changes with composition,

- shifts with temperature,

- evolves with fouling.

Examples:

- a reactor generates more heat at higher conversion,

- a column requires more reboiler duty at higher reflux,

- a cooler duty rises in summer due to warmer utilities.

Quantification must account for ranges, not single values.

Temperature Is the Driver, Not the Measure

Temperature is the most visible thermal variable, but it is not the most informative.

Heat transfer depends on:

- temperature differences,

- temperature profiles,

- local temperature gradients.

Two systems with the same inlet and outlet temperatures can have very different internal heat transfer behavior.

This is why experienced engineers look beyond temperature readings when judging performance.

Temperature Profiles Define Real Behavior

In any piece of equipment:

- heat transfer rate changes along the path,

- temperature difference shrinks or expands,

- local limitations appear.

Examples:

- exchangers lose driving force toward the outlet,

- reactors develop hot spots,

- furnaces experience uneven tube heating.

Quantification must consider how temperature changes through the equipment, not just end points.

Ignoring profiles leads to:

- undersized equipment,

- unexpected hot spots,

- poor control response.

Why Average Temperature Difference Is a Compromise

To simplify spatial variation, engineers use average temperature differences.

This is a practical necessity — but it is also a compromise.

Average values:

- hide local extremes,

- mask peak heat flux,

- smooth out critical gradients.

This explains why:

- equipment meets average duty but fails locally,

- tube metal temperature exceeds limits,

- fouling accelerates in specific zones.

Averages are useful tools, not truths.

Heat Transfer Coefficients Are Not Constants

Another common mistake in quantification is treating heat transfer coefficients as fixed properties.

In reality, coefficients depend on:

- flow rate,

- fluid properties,

- fouling condition,

- phase behavior.

As operating conditions change, coefficients change.

This is why:

- exchangers perform well at design load but poorly at turndown,

- startup behavior differs from steady operation,

- cleaning restores capacity.

Quantification must acknowledge variability.

Resistance-Based Thinking Improves Quantification

Effective quantification views heat transfer as a series of resistances:

- fluid-side resistance,

- wall resistance,

- fouling resistance,

- external resistance.

The largest resistance governs the rate.

This approach explains why:

- increasing flow sometimes helps,

- sometimes does nothing,

- sometimes worsens performance.

It also explains why “adding area” does not always solve problems.

Time Matters in Heat Transfer Quantification

Most calculations assume steady state.

Plants rarely operate at steady state.

Startup, shutdown, disturbances, and load changes introduce time dependence.

Thermal inertia means:

- metal lags fluid temperature,

- response is delayed,

- overshoot occurs.

Quantification that ignores time effects leads to:

- aggressive startups,

- thermal shock,

- unstable control.

Dynamic behavior is part of real quantification.

Why Safety Margins Exist

Heat transfer calculations always include margins.

These margins exist because:

- properties are uncertain,

- fouling is unpredictable,

- operating conditions drift,

- measurements are imperfect.

Margins are not inefficiency.

They are recognition of uncertainty.

Plants that remove margins in pursuit of short-term performance often pay for it later.

Quantification Links Design, Operation, and Maintenance

Heat transfer quantification is not a one-time design task.

It influences:

- operating limits,

- cleaning intervals,

- utility planning,

- debottlenecking decisions.

As equipment ages:

- resistance increases,

- margins shrink,

- quantification must be revisited.

Plants that treat heat transfer as static gradually lose performance.

Owner Perspective: Why Quantification Affects Profitability

From an ownership standpoint, quantification determines:

- energy consumption,

- achievable throughput,

- equipment life,

- reliability.

Underestimating heat transfer:

- causes chronic bottlenecks,

- forces conservative operation.

Overestimating heat transfer:

- leads to premature failures,

- increases risk and cost.

Balanced quantification protects both production and assets.

Final Perspective

Quantifying heat transfer is not about perfect equations.

It is about:

- recognizing variability,

- respecting limitations,

- understanding where numbers come from,

- knowing where they fail.

Plants that quantify heat transfer thoughtfully:

- operate closer to optimal,

- respond better to change,

- avoid repeated surprises.

Plants that rely on single numbers and averages often struggle without understanding why.

This knowledge is not advanced theory.

It is practical engineering judgment.

And it is essential for anyone responsible for real process plant performance.

We have discussed how heat transfer is quantified in process plants and how engineers convert physical heat flow into measurable design and operating terms.

The next step is to look closely at one of the most commonly used — and most misunderstood — quantities in thermal engineering.

This article explains what heat duty represents in real plant situations, how it is used in specifications and calculations, and why misunderstanding it leads to oversizing, undersizing, and poor thermal performance.